Kodama Kibō: The Japanese-Style Painter Who Persistently Explored

Peonies

Kodama Kibō was born in Hiroshima prefecture in 1898. Losing his parents as a child, he was raised by his grandparents, and after his family lost their fortune, he taught at his village’s elementary school when he was around 17 and 18 years old. He left his hometown for Osaka in 1916, and moved to Tokyo the following year, where he supported himself as a student. However, he aspired to study painting, a passion of his, after his grandfather’s death, and became an apprentice to Kawai Gyokudō in 1919, devoting himself to studying alongside other apprentices such as Isobe Sōkyū. His work was selected for the Teiten exhibitions for the first time at the third exhibition in 1921, and he exhibited his works every year, earning himself a special prize at the ninth exhibition in 1928. He was recommended as a member of the Teiten committee in 1931, and was nominated as one of the judges in 1932. Although he initially created ink wash paintings in the style of the Northern School, he was motivated by the Shinkō Yamato-e Movement to immerse himself in studying yamato-e, and established his own painting style that combined line drawing, colors, and realism. During this time, he organized the Boshin-kai with Gyokudō as his consultant and became active in the art scene, widening his range by exploring bird-and-flower, historical portrait, and bijin-ga paintings on top of Sansui-ga landscape paintings. After the Second World War, he presented his western-style expressions with ‘Shitsu-nai (Indoors)’ (1952), which won him the Geijutsu-in Award, and upon traveling abroad from 1957 to 1958, he began incorporating abstract expressions.

In 1950, he merged the Kokufū-sha and the Shinsui-juku to establish the Nichigetsu-sha. Kibō became a member of the Geijutsu-in in 1959, and poured his soul into Buddhist paintings in his last years. He died in 1971.

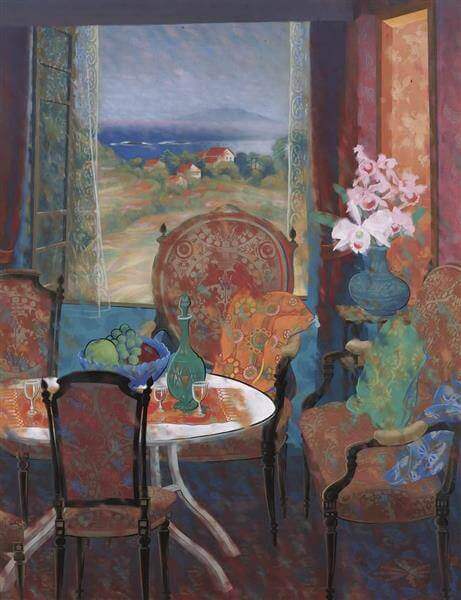

This painting depicts three large peony flowers that are in full bloom in different colors in a thicket, which harmoniously covers the entire canvas in ultramarine and verdigris shades, with the buds looking as if they can slip out of view. The scene is captured mostly through simply painting colors on top of each other. However, the exquisite lines that are on small parts of the pistils, stamens, and petals add a distinctive touch to the painting, and this is one of Kibō’s representative works along with ‘Shitsu-nai (Indoors)’. The work is a signifier of one of the many high points in his artistic career, and in fact, looks as if to hint on the abstract expressions that later take place in his works more than ‘Shitsu-nai (Indoors)’ does. The bold appearance of the peonies, known as Fūkika, are captured in a very impressive manner, and makes the work a modern piece of flower painting.

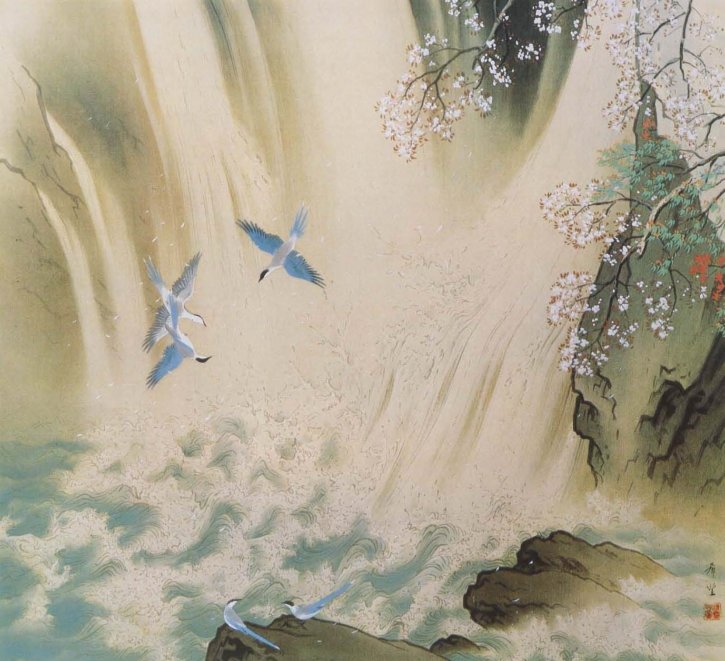

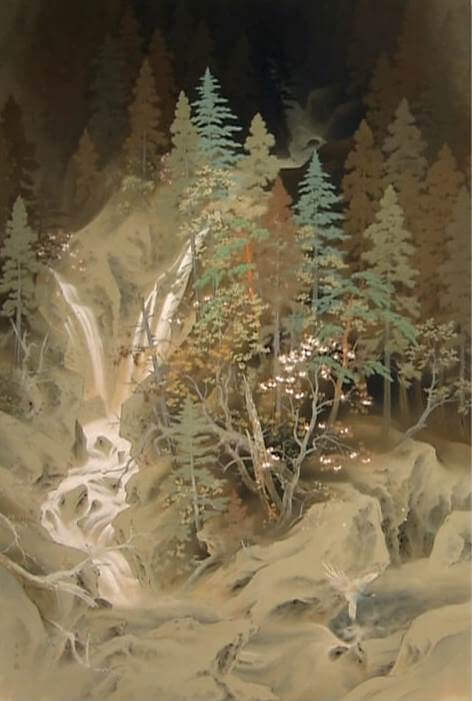

‘Sensei Chōgo (Spring Voice and Birds Sing)’

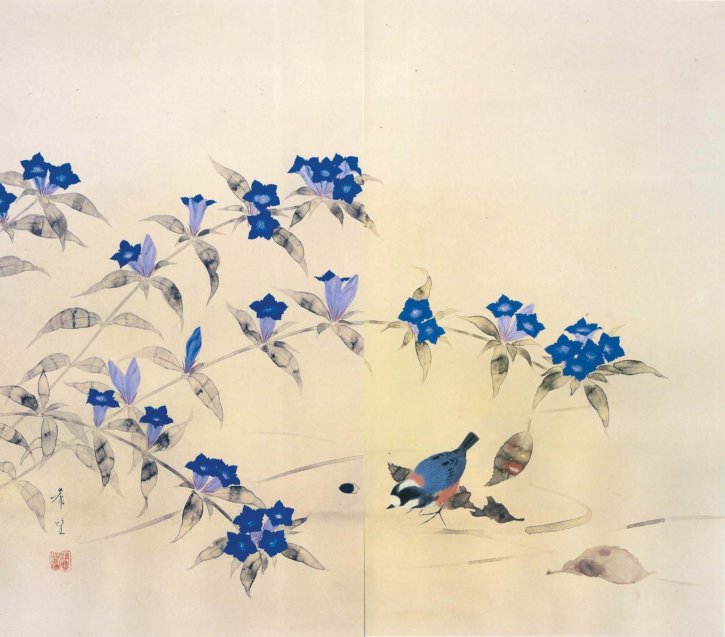

‘Shintō (New Winter)’

‘When I first started learning to paint, I mainly painted Sansui. The second most painted were birds and flowers, and around the time I only painted these two genres and started to create bird-and-flower paintings as much as Sansui paintings, I somehow became interested in portrait paintings, and in recent years, I would sometimes create period genre paintings, but I am only a poorly skilled enthusiast whose works are inadequate, embarrassing, and not worthy of mention.’ (words by Kodama Kibō)

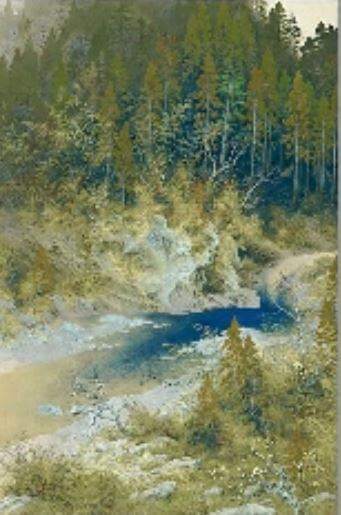

By taking a closer look at Kodama Kibō’s (1898-1971) career from his first Teiten exhibition in 1921, and mainly at the works that have been selected for Teiten and Shin-bunten exhibitions, it can be observed that he did indeed mostly exhibit Sansui paintings. Yet, from around 1933, paintings of birds, flowers, and animals became more prominent, and portrait paintings come into presence from 1946. Considering how Kibō’s career later evolved from western-like expressions to abstract expressions, this evolution of his painting style during the pre-war Shōwa period may have been a mere prelude to what took place later. Nonetheless, it seems that the transformation was drastic enough to surprise the people of that time. Some of the works that are especially captivating from this period are a series of works from ’Seishū (Mid-Autumn,)’ which earned him a special prize at the Teiten exhibition in 1928, to ‘Boshun (Late Spring,)’ ‘Senshun (Early Spring)’ (1930), ‘Hisen Sōsō (Flowing Waterfall) (1931), to ‘Yama Toyomu (Echoing Mountain)’ (1932).

With detailed realistic touches, each work has water located in a dense forest, and is painted in dark colors, making it decorative and large-scale. Although the inspirations that Kibō gained from Shinkō Yamato-e, a painting genre that was highly praised during that time, and especially the works of Yamaguchi Hōshun, are evident in these works, in each work lies his very own respect towards nature.

‘Spring Voice and Birds Sing’ is also a piece along the line of this painting style. The painting depicts several Azure-winged magpies playing in a pool of water from a tall waterfall, and mountain cherries hanging from the side with their petals in the air. The roars of the waterfall, the chirps of the Azure-winged magpies, the silently falling petals, and the strange contrast between the enormity of nature and the smallness of life, bring out powerful energy out of the painting that feels as if it is trying to expand itself out of the canvas. Although he showed his inclination towards works that depicted nature with birds and animals as part of it, notably in works such as ‘Kareno (Desolate Field,)’ which depicts a fox, his Sansui and bird-and-flower paintings became truer to their genres, and his painting style changed to become lighter and more modest, separating itself from dark colors and detailed touches.

‘Shintō (New Winter)’ is thought to be from around this time, which is after 1935, during the Shōwa period. Composed of a rather typical format of bird-and-flower painting, the work also thoroughly captures the tender air of Japan’s hills and fields in autumn. Bright blue flowers are in full floom in a dignified manner from the stems of Japanese gentians that have emerged from crawling up the ground. The leaves, resembling shiny bamboo leaves, are skillfully captured utilizing sumi ink and the *tarashikomi technique, and the several curves carelessly placed on the ground suggest that there is dry grass there. There are also fallen leaves and an acorn, and beside them is a delicately depicted varied tit that is looking for food. However, as Kibō has made clear in the following words, the work is nothing unpolished, and is rather lively: ‘In the case of bird-and-flower paintings, my biggest aim is to pay attention to their liveliness and movements. Painting live flowers and birds, that is my constant wish, and that is what I am devoted to.’ Expressing the soothing air of autumn and nature in a rhythmical manner, the painting is a fine piece of work.

- Tarashikomi: A high-level technique of Japanese-style painting for attaining natural blur by making use of the difference in the specific gravity of pigments.