Mizuno Toshikata: The Ukiyo-e Artist Who Survived the Meiji Period

Contents

- 1 Mizuno Toshikata’s Early Life

- 1.1 The Apprentice of ‘The Last Ukiyo-e Artist’

- 1.2 The Ukiyo-e Artist Who Does Not Know The Edo Period

- 1.3 Became an Apprentice of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi at the Age of 14.

- 1.4 The Death of His Father, and Re-Entering Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s Place

- 1.5 Debut as a Painter at the Age of 19

- 1.6 Rise to Fame as an Illustrator

- 2 Mizuno Toshikata and His Masters

- 3 The Time Period which Mizuno Toshikata Lived

- 4 Mizuno Toshikata and Ukiyo-e

- 5 Involvement with the Japanese Art Scene

- 6 The Apprentices of Mizuno Toshikata

Mizuno Toshikata’s Early Life

The Apprentice of ‘The Last Ukiyo-e Artist’

When it comes to ukiyo-e artists, what comes to mind may be the Edo period. However, they were in fact active during the Meiji period as well. Mizuno Toshikata is one of the representative ukiyo-e artists of the Meiji period.

Mizuno Toshikata’s master was Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, also known as ‘Bloody Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’ for capturing gruesome scenes. Tsukioka Yoshtoshi’s master was Utagawa Kuniyoshi, who is popular for his bizarre style of work.

Since he was skilled in musha-e, meaning ‘images of warriors,’ he was also called ’The Utagawa Kuniyoshi of Musha-e’ and prospered as an ukiyo-e artist representative of the late Edo period.

Despite coming from two generations of remarkable ukiyo-e artists, Mizuno Toshikata’s name is not widely known to the general public. He lived a short life of 43 years and was only active for a short period of time. The reason behind this is thought to be the fact that he was not active during the Edo period, which differs from the commonly perceived image of ukiyo-e artists.

However, he did, as a matter of fact, make great contributions to the world of ukiyo-e.

His master, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi is also referred to as ‘The Last Ukiyo-e Artist.’ Debuting in the final years of the Tokugawa Shogunate and flourishing towards the early Meiji period, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi was ‘An Ukiyo-e Artist of Edo,’ given life and nurtured by the Edo period.

On the other hand, his apprentice, Mizuno Toshikata, was born right before the Meiji Restoration, and the country had shifted to the Meiji period by the time he had grown out of his infancy. This made him the first ukiyo-e artist in ukiyo-e history to not know of the Edo period. The Meiji period was also a time when western civilization surged into the country, drastically changing the structure of society and values of people. In a society that was suddenly changing, ukiyo-e’s popularity began to decrease.

The Meiji period was not an easy time to live in for Ukiyo-e artists who carried the now-forgotten Edo culture on their shoulders. Determined to live the Meiji period as an ukiyo-e artist, Mizuno Toshikata studied the art from the works of not only Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, but also many other artists that came before himself, and widened platforms for ukiyo-e artists of the Meiji period.

While the producers of ukiyo-e, known as ‘the Medium of Edo,’ were in decline, a new medium came to replace it — letterpress printing. Mizuno Toshikata then became popular and took the society by storm as ‘illustrators’ through providing illustrations to new mediums, such as newspapers, magazines, and books.

Furthermore, Mizuno Toshikata unfolded a series of activities to seek artistic value in ukiyo-e. This was due to the ukiyo artists’ need to find themselves a place in the Japanese painting industry, called the ‘Nihon Gadan (Japanese art scene) .’

Ukiyo-e was an art form that had continued to endeavor, contrive, and evolve for nearly 200 years as the medium for the masses. What Mizuno Toshikata did was bring in his work of sophisticated techniques and ideas into an exhibition by the ‘Nihon Gadan (Japanese art scene)’ to question its artistic values.

The techniques that Mizuno Toshikata cultivated through ukiyo-e were also highly acclaimed among the ‘Nihon Gadan (Japanese art scene)’ . He was able to prove how ukiyo-e artists could challenge themselves in a scene that competes for artistic values. With this achievement, a path was paved for the ukiyo-e artists to survive in the Meiji period art scene.

This gave hope to the artists of Meiji’s declining ukiyo-e industry. Mizuno Toshikata was an ukiyo-e artist who also played an active role in the art scene as a painter of nihonga (Japanese-style painting).

As we follow the life of Mizuno Toshikata, we will also introduce his masterpieces.

The Ukiyo-e Artist Who Does Not Know The Edo Period

Mizuno Toshikata was born in 1866, two years before the Meiji Restoration, in Edo.

During his childhood, Japan was in a period of upheaval. The restoration of imperial rule took place when he was a year old, the Boshin War, the fall of Edo, and other historically significant incidents which led to the fall of the Edo shogunate and the birth of the new Meiji government, happened when he was two years old.

Mizuno Toshikata grew up in the city of Edo (Tokyo,) where life was changing everyday under the surge of westernization. The school system was established when he was six years old, making him a part of the earliest generation to receive modern education.

The perfect material to have when talking about Mizuno Toshikata’s life is the autobiography, ‘The Chronicle of Koshikata,’ written by his apprentice, Kaburagi Kiyokata.

Kaburagi Kiyokata was an exceptionally well-known apprentice out of all the students that Mizuno Toshikata had. Having left behind many essays, he was also a gifted writer.

His autobiography mentions many things about his master, Mizuno Toshikata. Even more, it documents almost his whole life from childhood to death at the age of 43.

Not only is the documentation detailed, one can also tell how Kaburagi Kiyokata deeply loved and respected his master, Mizuno Toshikata, from every bit of the sentences.

With Kaburagi Kiyokata’s materials as reference, let’s unravel the life of Mizuno Toshikata.

Became an Apprentice of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi at the Age of 14.

Mizuno Toshikata’s father was a master of plasterwork. Mizuno Toshikata’s mother separated with his father early in his life. Thus, Mizuno Toshikata lived with his father’s second wife and his half siblings (numbers unknown.)

To take over the family business, Mizuno Toshikata would help his father’s profession as a plaster worker from a young age. However, he loved to draw so much that he would draw at any given free time — he eventually aspired to become an artist.

At the age of 14, he became a live-in apprentice for the renowned ukiyo-e artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, and started leading his life as an ukiyo-e artist. However, his master was someone nicknamed ‘Bloody Tsukioka Yoshitoshi.’ In fact, he was recognized for his avant-garde style of work, and known for being disorderly and violent in his private life.

Unfortunately, Mizuno Toshikata became an apprentice during a time in which his master’s life was especially disordered. Numerous incidents of oppression from Tsukioka Yoshitoshi towards Mizuno Toshikata have been told. For example, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi often called him a ‘plaster worker’ rather than by his name, and swung wooden poles around him when Yoshitoshi was displeased with something. As a matter of fact, it seems that Tsukioka Yoshitoshi did not properly teach him painting to begin with.

Mizuno Toshikata’s father made his son, who was supposed to take over his position as a plaster worker, make visits to Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s place because he said that he ‘wants to be an artist no matter what.’ Nevertheless, there was no point to anything if his son’s teacher Tsukioka Yoshitoshi wasn’t teaching him how to paint, and was instead indulging himself with the women of Edo’s red-light district, Yoshiwara. As a man from downtown Edo with a craftsman’s mentality, Toshikata’s father found the situation infuriating, and took his son home the following year.

The Death of His Father, and Re-Entering Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s Place

Although he may have been forced to quit being Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s live-in apprentice, it did not mean that his determination had faded.

He continued to study in order to become an artist, and studied porcelain painting, a method of painting on porcelain, and Nanga painting, a school of Japanese painting inspired by Chinese painting that flourished after the mid Edo period.

However, when Mizuno Toshikata was 16, his father passed away. He re-entered Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s place a few years later. He began paving his way to become an artist again after the death of his father, whose stoic craftsmanship mentality pulled him out of his life as a live-in apprentice.

Fortunately, by then, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi had recovered from his corrupt life and was back to painting with an improved lifestyle.

In 1882, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi exhibited his work, ‘Fujiwara no Yasumasa Playing His Flute in the Moonlight,’ at the first Naikoku Kaiga Kyōshinkai Exhibition. The work was highly acclaimed, and he gained recognition not only as a block print artist, but also as a painter.

Regardless of this, many of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s apprentices were leaving him because of his rough attitude and violent language. It was in the midst of this that Mizuno Toshikata returned to him. He had a backbone, was reliable, honest and hardworking, making Tsukioka Yoshitoshi appreciate him well. According to Kaburagi Kiyokata, Mizuno Toshikata’s personality was the exact opposite of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s — he disliked flamboyance, valued persistent efforts, and had the backbone of a warrior despite coming from a family of craftsmen.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi took a liking to Mizuno Toshikata, for he was never defeated by any of the strict shouting that he was given, and allowed him to re-enter as an apprentice.

Debut as a Painter at the Age of 19

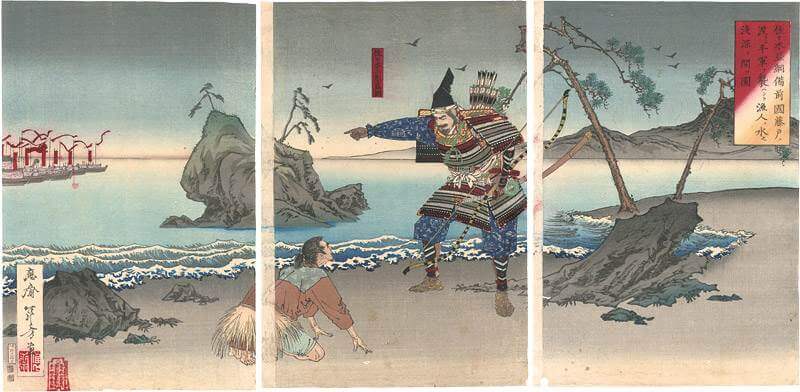

Mizuno Toshikata’s actual debut as a painter took place in 1884, when he was 19 years old.

He published a three-piece nishiki-e painting (‘Sasaki Moritsuna Asking Fisherman to Reveal the Shallows Where His Troops can Cross and Attack the Taira Forces at Fujito in Bizen Province.’)

Until then, he undertook small jobs such as taking part in illustrating picture books as Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s assistant. Given that, his debut was something very magnificent — his work was a three-piece nishiki-e that he painted as his own.

Kaburagi Kiyokata believed that the then-unknown Mizuno Toshikata would not have had support from the producers if it were not for the good word that Tsukioka Yoshitoshi put in on his behalf.

The exceptionally warm welcome he received at his debut continued on, as he published three sets of three-piece nishiki-e works titled ‘Snow, Moon, and Flowers’ and another three-piece nishiki-e depicting Kusunoki Masashige welcoming the emperor.

He was treated exceptionally well as a new-coming artist. This all came to fruition because of his master Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s strong trust and expectation on his talent and skills.

Rise to Fame as an Illustrator

In 1885, the following year of his debut, he continuously released works as the number of commissions increased drastically. He released a diverse range of works, from single-piece paintings to illustrations for print books, under various themes.

His illustrations for print books were the first to be acknowledged. He provided many illustrations for historical books. To add on, he worked on many different subjects — for example, a story about a merchant. On the other hand, he also released a single-piece nishiki-e with a historical subject, which too was highly acclaimed.

Additionally, in his series ‘Kyōdō Risshi no Motoi’ published from 1883 to 1889, he collaborated with ukiyo-e artists that are representative of the Meiji period, namely Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, Inoue Tankei, and Kobayashi Kiyochika.

A source that suggests his sudden rise to popularity is ‘Tokyo Ryūkō Saiken Ki (Detailed Guide to Tokyo’s Trend)’ — a book that ranks various shops and businesses of that time.

The book also included a ranked list of popular ukiyo-e artists. Although his master Tsukioka Yoshitoshi was at the top of the list, Mizuno Toshikata gained instant popularity, which was enough for him to make it into 12th place despite being a newcomer.

Along with his master, Mizuno Toshikata joined daily newspaper ‘Yamato Shimbun’ as its illustrator when it was launched in 1886. Besides reporting the latest news, ‘Yamato Shimbun’ also printed entertainment articles related to novels, show business, and gossip.

‘Yamato Shimbun’ was launched by journalist and author Jōno Saigiku, who is the father of Mizuno Toshikata’s apprentice Kaburagi Kiyokata. Kaburagi Kiyokata, who later in his life becomes a leading figure in the Japanese painting scene as an expert of bijin-ga, was still a child back then, and was not yet under Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. Watching the works of Mizuno Toshikata and Tsukioka Yoshitoshi through his father, Kaburagi Kiyokata becomes Mizuno Kiyokata’s apprentice, an illustrator for ‘Yamato Shimbun,’ and eventually documents his master’s life.

Due to financial difficulties, producers of hand-printed books in Japanese-style binding fell into decline in the twenties of the Meiji period. In exchange, what came after this were ‘publishers,’ who issued books in western-style binding using printing machines. Ukiyo-e artists had no choice but to adapt to this change in the industry.

After the literary magazine ‘Bungei Kurabu (Literary Club)’ was launched by Hakubunkan in 1895, Mizuno Toshikata became responsible for creating illustrations for its famous novelists. He illustrated for many notable authors, such as Izumi Kyōka, Kōda Rohan, Yamada Bimyō, and Futabatei Shimei.

Together with fellow illustrator Ogata Gekkō, he was celebrated as one of ‘the matchless talents of illustration’ because of his many captivating works, and it was even rumored that ‘magazine sales would rise if it is illustrated by Mizuno Toshikata.’

Mizuno Toshikata and His Masters

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, the Master of Ukiyo-e

Mizuno Toshikata took after the teachings of one of the most prestigious ukiyo-e schools — the Utagawa school.

Although Tsukioka Yoshitoshi did not adopt ‘Utagawa’ as his last name, he was given the letter ‘芳 (Yoshi)’ from Utagawa Kuniyoshi, and Mizuno Toshikata was given the letter ‘年 (Toshi)’ from Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. As this explains, the three artists are of the same lineage. Mizuno Toshikata gave the letter ‘方 (Kata or Pō)’ to his apprentices, with the names ‘Kaburagi Kiyokata,’ ‘Ikeda Terukata,’ and ‘Arai Kanpō.’

Mizuno Toshikata took over the traditions of the Utagawa school. At the same time, however, he also incorporated his own ideas, expressions, and techniques that he learned from other artists into his works. The Utagawa school is, after all, known for its lineage of reformers that defied conventional methods.

His predecessor Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, and the generation before him, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, are known for having broken down practices that were common in ukiyo-e, and establishing new frontiers.

For example, his master Tsukioka Yoshitoshi studied not only ukiyo-e, but also the Shijō school of Nihonga painting, and valued sketching. He is known for having visited a battleground of the Boshin war, sketching a soldier’s corpse.

Mizuno Toshikata, succeeding the two reformers Utagawa Kuniyoshi and Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, did not take any frantic actions that would be remembered by his successors, perhaps because of his innately earnest personality.

Yet, Kaburagi Kiyokata, who always knew his master’s approach to work, commented that ‘nobody studied the basics of illustration as genuinely as Mizuno Toshikata did.’

The focal point to Mizuno Toshikata’s reformation boils down to how he studied the basic techniques of other schools and genres. In that sense, Mizuno Toshikata had a few other masters besides Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. Here, we would like to introduce his masters from different schools and genres.

Yamada Ryūtō of Porcelain Painting

After he was separated from Tsukioka Yoshitoshi by his father, Mizuno Toshikata temporarily worked as a rough sketch artist for porcelain paintings.

During this time, he studied the porcelain paintings of Yamada Ryūtō, who was the apprentice of Nihonga painter Suzuki Gako.

Suzuki Gako was an apprentice of Tani Bunchō, and is said to have succeeded the lineage of Nanga, a genre influenced by Chinese painting.

Shibata Hōshū of Nanga (Bunjinga)

Mizuno Toshikata also studied from the Nihonga painter, Shibata Hōshū.

Shibata Hōshū was a painter who studied the paintings of the Kishi school from Kida Kadō, and Nanga (a school influenced by Chinese painting) from Murata Kōkoku.

Watanabe Seitei

What is exceptionally rare is the fact that he received lessons from Watanabe Seitei. He was a Nihonga painter skilled at painting birds and flowers, and was called the solitary artist.

He rarely took in apprentices, and it is said that Mizuno Toshikata was his only one. It seems that Watanabe Seitei had ties with Tsukioka Yoshitoshi through the magazine ‘Bijutsu Sekai (Art World),’ in which he was the chief editor, resulting in Mizuno Toshikata studying under him.

Mizuno Toshikata studied techniques and knowledge from different schools, and made them his own. As a result, he was able to establish a new frontier that went beyond the limits of the Utagawa school and ukiyo-e.

The Time Period which Mizuno Toshikata Lived

In the Midst of Civilisation

Although it may seem that his life as an ukiyo-e artist took off smoothly, it does not change the fact that the Meiji period was a tough time for these artists.

In the midst of civilisation, all industries underwent drastic change, including the world of publishing and media. The change hit the world of ukiyo-e, which reigned as the main medium of the Edo period, especially hard, and put it in an extremely precarious position. The subjects of ukiyo-e paintings were tourist attractions and ‘celebrities’ that people commonly admired, such as popular actors, sumo wrestlers, and prostitutes.

Ukiyo-e paintings functioned as platforms for news, advertisement, and entertainment. However, it was now photographs that captured celebrities, and newspapers replaced ukiyo-e works that depicted current affairs (jikyoku-e) to report incidents. As letterpress printing was coming into existence, production of picture books in woodblock printing was also reaching an end.

It comes without saying that the people who supported the medium — artists, woodblock carvers, printers, and even the producers that supervised them — were about to lose their reason for being in a new era.

’The Beginning of the End’ of Ukiyo-e

The year 1887 is said to be special for Japan’s publishing industry. This was the year in which the publication number of ‘western’ books in letterpress printing, a newly-found technology at that time, overtook those of traditional, hand-printed ‘Japanese’ books, and is known as ‘the year Japanese books went extinct.’

The positions of the two never changed.

The culture and industry of woodblock printing fell into decline along with Japanese books. These books are fully handmade by craftsmen, from carvers creating block copies, and printers printing block patterns onto paper. Due to this, Japanese books were produced by local shops in cities, and kept small in scale.

On the other hand, mass production was possible with western books since they were made by mechanically printing (pressing) blocks of metallic letters onto paper. It was in the Meiji twenties when wealthy ukiyo-e producers started their businesses as ‘publishers.’

This change in the industry was of great concern for Mizuno Toshikata, who was 22 years old at the time, and had only recently found himself a place in the world of Japanese books. There was no doubt that he would have to downsize his business, if he were to fixate on Japanese books and continue on with its hand-printing techniques.

However, if he were to work along with the new publishing medium, it meant that there would no longer be a path left for printers and other craftsmen to survive.

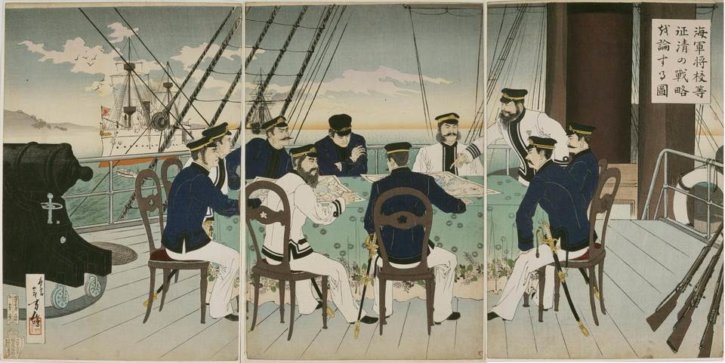

Prolific Painter of the First Sino-Japanese War

It was under these circumstances that the war between Japan and China’s Qing dynasty started in 1894. As requested by his producers, Mizuno Toshikata published many nishiki-e paintings of the First Sino-Japanese War. They were not painted upon actually interviewing people in the battlegrounds, but were created out of his imagination of the war, which was based on information he collected from newspapers and such.

Ukiyo-e artists were, by nature, expected to be commercial artists that responded to the requests of the producers, painted whatever the customers wanted to read about and whatever the time period desired. In addition, they were, at the same time, considered to be documenters of time as their works captured the atmosphere of every time period they were present in.

These military paintings too, are considered to be valuable documents that depict the atmosphere of the time period, including its passion and wild excitement.

The Death of His Master, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Mizuno Toshikata’s master, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, passed away in 1892, two years before the First Sino-Japanese War. This marked the end of an era, or to be more precise, the end of an era of ukiyo-e.

In his book, Kaburagi Kiyokata recalls how ‘ezōshiyas,’ shops that sold books by ukiyo-e artists, fell into visible decline after a huge trend that took place around 1894, of war-related works from the First Sino-Japanese War.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, who was known as ‘The Last Ukiyo-e Artist,’ left this world without witnessing the end of ukiyo-e with his own eyes. After Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s death, suggestions were made for Mizuno Toshikata to succeed his name, but this was never actualized.

Nonetheless, it was agreed upon by everyone that he was the one to succeed Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. One can easily imagine the kind of attention that was drawn to Mizuno Toshikata, to see what his next move would be in the final days of ukiyo-e as Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s most likely successor.

As platforms for ukiyo-e artists decreased, Mizuno Toshikata started illustrating for newspapers, magazines, and books issued by ‘publishers,’ which were starting to prosper at the time. These publishers were, without a doubt, the same people that drove Japanese books to ruin, but by then, he was left with no choice.

Mizuno Toshikata created illustrations and front covers for numerous novels in an earnest and steady manner. His great efforts earned him the title of ‘the illustrator that determines a book’s sales,’ and as mentioned earlier, he came to be known as a popular illustrator alongside Ogata Gekkō.

The apprentices of ‘The Last Ukiyo-e Artist,’ and the generation that followed them, indeed, had to live through a time period in which the art movement was under the threat of extinction.

Mizuno Toshikata and Ukiyo-e

An Expert of Bijin-ga

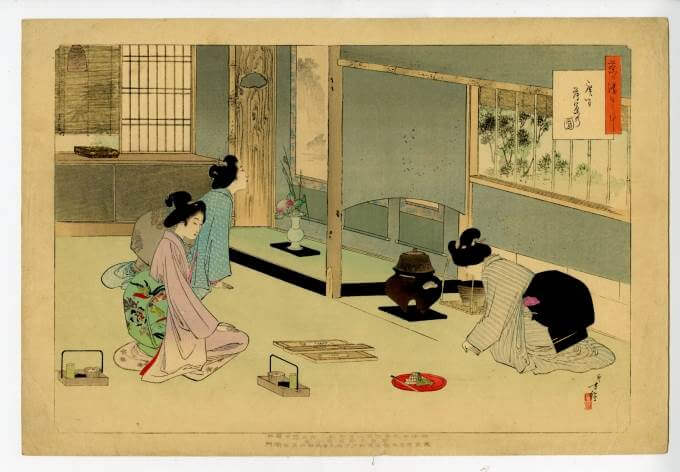

Mizuno Toshikata is known as an expert of bijin-ga, and it is even said that his ability to capture elegant and sophisticated women is incomparable .

Here, we would like to introduce some of the bijin-ga portraits that represent his notable series of works.

‘Thirty-Six Examples of Beauties’ is a series of 36 paintings, and is one of his masterpieces. Every piece of the series captures a ‘bijin (beautiful woman,)’ each from a different era of the Edo period, in clothing and hairstyles specific to the time.

‘Daily Practice of the Tea Ceremony’ is a series that introduces the customs of Japanese tea ceremony. The series was, in a sense, a guidebook made to spread the culture of tea ceremony, which was male-oriented until then, to women.

‘Modern Beauties’ is a series that portrays the lives of women in every month of the year. As suggested by the term ‘modern,’ the series depicts women in their contemporary lives, and captures clothing and hairstyles that were in fashion during the Meiji 30s. This series documents the atmosphere specific to its time period, showcasing Mizuno Toshikata’s significance as an ukiyo-e artist and a documenter of his times.

History Paintings Were His Specialty

According to his beloved pupil Kaburagi Kiyokata, although Mizuno Toshikata made a name for himself as an expert of bijin-ga, that was not what he actually desired to paint, and his specialty lay elsewhere.

Ever since his debut, Mizuno Toshikata had made historical paintings. Additionally, whether it be hand-painted or printed, most of the works that he presented in exhibitions by the Japanese-style art scene after the Meiji 30s, were history paintings. Thus, there is no doubt that history paintings were Mizuno Toshikata’s specialty.

For Mizuno Toshikata, who was earnest and did not pick up any pastimes, his only hobby was collecting historical materials. He purchased weapons and armor, objects that were far from being practical under the Edo period’s peaceful time, and used them as references for his paintings. This suggests his extraordinary passion for historical paintings. As a matter of fact, Mizuno Toshikata once begged for Matsubara Sukehisa, an expert of ‘Yūsoku Kojitsu,’ the study of ancient court and military practices, to give him lessons on the field.

On top of this, he also formed ‘the historical genre painting club’ with painter and expert Kobori Tomoto, further reassuring his extensive knowledge and passion.

Involvement with the Japanese Art Scene

Nihon Bijutsu-in and Nihon Kaiga Kyōkai

It was from around 1897 that Mizuno Toshikata took on a new challenge.

He became more active in academic organizations of nihonga painters, such as Nihon Bijutsu-in and Nihon Kaiga Kyōkai. The former was founded by Okakura Tenshin and other authority figures of the art style. Eventually, Mizuno Toshikata started to submit his works to the organizations’ exhibitions.

It is unclear as to why Mizuno Toshikata approached these academic art groups despite already being a well-established illustrator in the art scene. However, based on Kaburagi Kiyokata’s notes, it seems that there was a point in which Mizuno Toshikata started to dream of presenting his works at exhibitions by the Japanese-style art scene. The paintings presented at the exhibitions were all highly acclaimed.

In 1898, he submitted his work to the fifth Nihon Kaiga Kyōkaiten Exhibition, and was awarded first prize.

In 1898, the first exhibition by the Nihonga-kai (Japanese-style art association) was held. Mizuno Toshikata had the honor to have his work presented to the Imperial House. The work was made right after the death of his wife.

Creating His Epic History Painting

Mizuno Toshikata lost his master, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, in 1892, and then his wife in 1895. Upon experiencing the deaths of his closest people one after another, he challenged himself to start on an epic painting with a historical theme, which was something that he had always wanted to explore.

These works were submitted to an exhibition of the Nihonga-kai, where he was awarded once again.

In 1899, he submitted his works to the seventh Nihon Kaiga Kyōkaiten Exhibition, and was awarded a bronze prize. His next award was in 1903, when he made submissions to the 13th exhibition and won a silver prize.

Even with consideration over the fact that he had always wanted to create history paintings, the question remains: why did he choose to submit them to academic exhibitions instead of publishing them as ukiyo-e works? It is believed that the circumstances which surrounded ukiyo-e at the time played a certain role in this decision.

Caught in a situation in which the ukiyo-e techniques that were continuously improved by his predecessors for over 200 years were falling into decline, Mizuno Toshikata felt that ukiyo-e artists were looked down on, compared to painters, that, for example, were from the Kanō school or the Maruyama school and catered to the Imperial Court, or studied in Tokyo Fine Arts School (later renamed Tokyo University of the Arts.)

Under such circumstances, Mizuno Toshikata, as an artist representative of the ukiyo-e world, found his way into the Japanese-style art scene and became an acclaimed figure there. The significance of an accomplishment this great is immeasurable. He improved the status of ukiyo-e and genre paintings, and paved a path for ukiyo-e artists to compete in the nihonga art scene.

The Apprentices of Mizuno Toshikata

The Genes of the Ukiyo-e Artist Left in the Japanese-Style Art Scene: Kaburagi Kiyokata, Itō Shinsui and Kawase Hasui

Mizuno Toshikata fostered many apprentices, and sent painters such as Kaburagi Kiyokata, Ikeda Terukata, Ikeda Shōen, Arai Kanpō, Mizuno Hidekata, Takeda Keihō, and Ōno Shizukata out to the world.

The lineage of ukiyo-e artists that continued on from Utagawa Kuniyoshi to Tsukioka Yoshitoshi was confronted by an era of great transformations under the Meiji Restoration, but Mizuno Toshikata kept it from perishing with his steady efforts.

This lineage of artists eventually connected ukiyo-e to the world of Japanese painting and its art scene, and provided a new platform for ukiyo-e artists to flourish in.

Mizuno Toshikata left this world at the mere age of 43, but he nurtured many apprentices including Ikeda Terukata, Ikeda Shōen, and Arai Kanpō.

His passion was passed down to his beloved apprentice Kaburagi Kiyokata, and afterwards came Itō Shinsui and Kawase Hasui. The lineage of artists grew to become an influential force on modern Japanese art.

The techniques that ukiyo-e cultivated over its many months and years stimulated and brought life to the Japanese-style art scene along with Western art.

Mizuno Toshikata may not have been able to live and die in the world of ukiyo-e as an ukiyo-e artist like his master Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. However, he lived in the world of nihonga as an ukiyo-e artist, and died as its newly-acclaimed painter and artist.