Katayama Gashū: The Nihon-ga Painter of Misfortune from Shiga Prefecture

Aoi-Zu (Hollyhocks Painting)

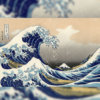

Katayama Gashū was born in the north of Shiga prefecture in 1872. Other than Gashū, he also has pseudonyms such as Unpō and Tetsugen. As Gashū’s family were farmers, he did farm work in the afternoon, and at night, he enjoyed sketching illustrations of Yanagawa Shigenobu and Katsushika Hokusai from his favorite picture book. The young man, who was a painting farmer, set out to Kyoto with determination, he knocked on the door of Kōno Bairei and formally began his training at 23 years of age. The following year after leaving for Kyoto, Kono Bairei had passed away, so he entered the academy of Imao Keinen, the master of bird-and-flower painting. Although his painting style was self-taught from the depths of the countryside, he distinguished himself under the wings of a good teacher, and he won the second prize at the Nihon Bijutsu Kyōkai Exhibition held in Tokyo in 1897. In November of that year, he left for Tokyo, was introduced to Hashimoto Gahō, and adopted the name Gashū. As his life was just about to start, there were no workers at his family home, and he eventually returned to farming the following year. From then on it was a life of cultivating on a sunny day and painting when it rained. Gashū married late at 54 years old, had three sons and a daughter, and lived a quiet and comfortable life — he passed away in 1942 at 71 years of age. At first, Gashu’s paintings were bird-and-flower paintings, and after genre paintings, he mostly painted landscape paintings and Taoist and Buddhist figure paintings in later years.

Aoi-Zu (Hollyhocks Painting) is thought to have been from around 1904. The drawing style is similar to Keinen’s one. Gashū won an award at an exhibition in Tokyo and knocked on the gates of Hashimoto Gahō but returned home to farming without counting the days and months of the year. He planted hollyhocks in his garden and devoted himself to sketching them in his spare time, but the only thing painted in this piece, other than the two white and pink-white hollyhocks, is a frog resting one of its leaves. This effectively and powerfully captures the hollyhocks on a summer day.

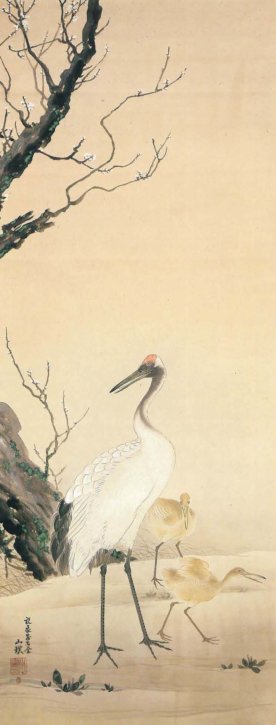

Ume ni Tsuru-Zu (Plum Tree and Cranes)

Gashū set out to Tokyo in 1897 and studied under Hashimoto Gahō, but returned to farming the following year — this painting was created in the New Year of 1899. The work was painted on New Year’s day after he was forced to return home from Tokyo, a place he had set out with aspirations to establish himself. The feathered chick and red-crowned crane are probably parent and child. The drawing depicts a peaceful crane parent and child with an old plum in the back, but to him, it seems that there was no other choice than to create a painting celebrating the safety of his family upon New Year. One can assume the reason why he was hesitant to use his pseudonym ‘Gashū’ here. In that year, Gashū had just turned 27 years old. Gashū painted with a focus on the bird-and-flower genre for only a few years. It may be that Gashū left Keinen’s side, set out to Kyoto, and studied under Gahō because wanted to paint landscapes and Taoist and Buddhist figure paintings. After he returned to farming, even while he was drenched in mud as a result of living a farmer’s lifestyle, he visited the museum during the off-season, sketched Japanese-Chinese masterpieces, and enthusiastically studied genre paintings. It was also around this time that he partook in Zen meditation at the Kyoto Kennin-ji Temple, and joined in with Ashizu Jitsuzen, a monk from the Eigen-ji Temple, to study poetry. Due to this, in his late years, Gashū painted a lot of figures of the Daoist and Buddhist religion that embodied the philosophy of Zen and created more ink wash paintings. There are not that many bird-and-flower paintings by Gashū, as they were mainly painted during the few years he was back home after failing to fulfill his ambition despite breaking free from self-studying in the countryside, getting a good teacher, and being determined to become a professional artist. Another reason is that he was far from being a prolific artist.

Unlike the paintings exhibited at the Nihon Bijutsu Kyōkai Exhibition, the combination displayed in ‘Ume ni Tsuru-Zu’ is interesting, with calm brushstrokes, and the fact that it is a work of serenity is comforting.

Kujaku-Zu (Peacocks Painting)

Gashū was at the gate of Imao Keinen in the spring of 1897. Under the master, he studied bird-and-flower painting. The ‘Kujaku-Zu’ (Peacocks Painting) was exhibited at the Nihon Bijutsu Kyōkai Exhibition in Tokyo and won the second prize. In the previous year, ‘Chōshun Sōkei-Zu’ (Rooster and Hen in Spring Painting) also won the second prize, which made this his second consecutive year of winning a top prize. With this, he heightened his confidence and set out to Tokyo, visited Hashimoto Gahō, and as aforementioned, became his apprentice. Moreover, Imao Keinen who was Gashū ’s master also received the second prize at the Nihon Bijutsu Kyōkai Exhibition in 1896 and 1897. It can be said that winning the same prizes as his master was what gave him the confidence and desire for Tokyo, a new world.

This painting is a work full of Gashū’s youth and overflowing ambition. The male peacock standing on the rock is firmly grasping it with its thick legs. The splendid tail feathers that are hanging down at the center of the image are running high, probably because they are struck by the wind. The essence of this painting is here. Due to the tail feathers of the male, only the tip of the tail and chest of the female resting in the grass under the rock can be seen, but the crossing composition of the male and female peacocks is well put together. The decorative nature of the peacocks is emphasized by only having spring orchids peeking out from the rock shadow. The only authentic bird-and-flower paintings by Gashū are the two pieces that were exhibited at the Nihon Bijutsu Kyōkai Exhibition. We can know how complete Gashū must’ve felt during these two years, and nonetheless, how shocking it was for him to have to return to farming and his home due to the family’s situation.

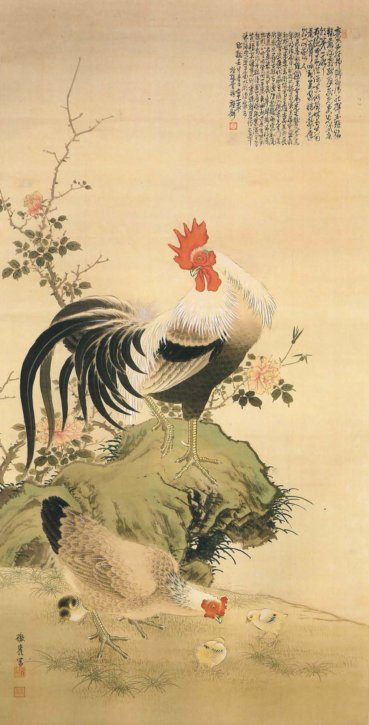

‘Chōshun Sōkei-Zu’ (Rooster and Hen in Spring Painting)

This piece was exhibited at the Nihon Bijutsu Kyōkai Exhibition of fall 1896, a year after joining the Keinen Academy, and was awarded the second prize. ‘Chōshū Sōkei-Zu’ (Rooster and Hen in Spring Painting) is also Gashū’s first piece on a silk canvas. There is also a piece by him painted on paper that consists of two chickens. It was painted three years before this one under the pseudonym Unpō and depicts a hen and her three chicks lined up in a line and look for food as they peck the ground. The piece is possessed by Fuse Art Museum in Shiga prefecture. The painting style of the chickens in this piece is the same as ‘Chōshū Sōkei-Zu.’ Likely, the piece from Gashū’s time as Unpō was originally a sketch that he made upon seeing the chickens look for food in his yard. This piece, created after he joined Keinen’s academy, was his first piece on silk, and shows a rooster on top of a rock, standing as if to look behind himself. Roses are placed behind the rock, undoubtedly making the layout of the piece that of a bird-and-flower painting.

The chickens and roses are painted accurately and are a magnificent piece of bird-and-flower painting. It could be said that this serves as a good example of how a good teacher can drastically change one’s paintings. Gashū won a prize the following year as well and used that as an opportunity to leave for Tokyo, where he studied under Hashimoto Gahō.