Itō Jakuchū’s Paintings 002: Artistic Career

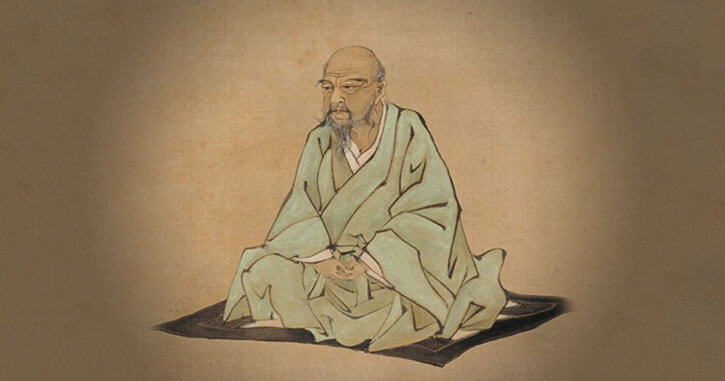

Let’s take a brief look at the career of Itō Jakuchū.

Born as the eldest son of the Masuya, a vegetable dealer on Kyoto’s Nishiki Street, Jakuchū was said to have not been interested in academic studies during his childhood and was not good at calligraphy or anything else in particular.

It is not known for certain when he became interested in painting, but he lost his father at the age of 23 and took over the family business as a vegetable dealer. It is believed that he started painting before that time and began to study specialized painting in his twenties.

However, it is unclear who the painter was who first taught him to paint, but it is thought that he may have studied with a town painter named Ōoka Shunboku, who was skilled in the Kanō school, or learned from his publications.

Furthermore, he is said to have independently studied the Song Yuan painting in Chinese painting, following the Kanō school.

Although there are paintings that actually copy Song-Yuan paintings, they seem to be strongly influenced by Ming-Qing paintings.

In particular, the composition imitating the finely detailed flower and bird paintings called Nanpin-ha (Nanping school), which was created by Shen Nanpin, who came to Japan from Qing China in 1731, was depicted.

The Nanpin school of painting was spread throughout Kinai (the provinces surrounding Kyoto and Nara) by the Ōbaku Zen monk, Kakutei, who learned it in Nagasaki, and it is thought that Jakuchū also learned from his paintings.

In this way, Jakuchū studied in detail the styles, painting techniques, composition, expression, and color techniques of many painters as a self-taught method of painting, incorporating them into his own paintings as nourishment.

Rather than being depicted on top of the painting in an undigested form, they were unified as his own medicine cabinet and became a unique form of painting. In other words, despite being filled with all kinds of era-specificity, schools, depiction techniques, and expression methods, a mysteriously unique painting style was completed, resulting in individualistic paintings. Pursuit that was not bound by existing forms and techniques can be seen.

During the period when Jakuchū devoted himself to painting, from the early to late 18th century, Japan was in a period of developing the samurai culture in Edo (modern-day Tokyo), moving away from the Kansai-centered culture of the past and creating a new culture in Edo.

The Genroku period was a time when the splendid Kansai culture and the new Edo culture coexisted in parallel, and after the first half of the 18th century, the political and cultural center gradually shifted to Edo.

In the latter half of the 18th century, when Jakuchū was active, as a result of the active exchange between the East and the West, the Kansai region yielded cultural leadership to Edo while forming a unique culture once again.

At that time, Jakuchū had the achievements of his predecessors in the East and West in front of his eyes, and by following their examples, he made further progress, and it can be said that he had an endless amount of things to incorporate and accumulate. Jakuchū must have studied the techniques and arts of his predecessors one by one, replacing them with his own.

It is unclear which work was Jakuchū’s first completed piece, but “Rooster and Hen in Snow” with the seal “景和 Keiwa” was listed as his earliest work from the surviving works. He subsequently worked on the “Peonies and Lilies” set, and painted the “Pine Trees with Pair of Chickens” around the age of 37.

Their production is said to have taken place between the Enkyō 4th year (1747) and the beginning of the Hōreki era (1751-), and at the age of 40, Jakuchū handed over the headship of his family’s green grocery business to his younger brother and retired.

He chose to devote himself solely to painting, but it may be more appropriate to call it a painting life rather than a painting career, as Jakuchū, who was financially well-off, never had to sell his paintings to make ends meet. This fact has a profound meaning as it is different from the attitude of other professional painters. It means that Jakuchū was able to maintain a consistent theme for his paintings throughout his life, that he could engage in expressive activities as he pleased.

After handing over the family headship, Jakuchū created the “Flowers and Twin Cranes,” “Gourd and Insect Group,” “Moon and Plum Blossoms,” “Rising Sun and Phoenix,” “Tiger,” “Crane,” “Dead Tree with Eagle and Monkey,” “Moonlit Night with White Plum Blossoms,” and “Playing Birds in Snow,” which were followed by the 30 pieces of Dōshoku Sai-e (Colorful Realm of Living Beings) . The “Dōshoku Sai-e,” which is also said to be his representative work, depicts plants and animals as the main theme and was painted by Jakuchū over approximately nine years, from the age of 43 to 51. In 1765, at the age of 50, Jakuchū donated these thirty works of the Dōshoku Sai-e (six of which were later donated) to the Shōkoku-ji temple along with three Buddha statues. Jakuchū was impressed by three Buddhist paintings of Shaka, Monju, and Fugen of Chō Shikyō (Chinese painter)in Kyoto’s Tōfuku-ji temple, and he imitated their brushwork to depict the true nature of flowers, birds, and insects in his “Dōshoku Sai-e.” To pass them down to future generations, he made a donation of them to the Shōkoku-ji temple. The “Dōshoku Sai-e” became a topic of public interest immediately after entering Shōkoku-ji, and Jakuchū himself had already become a renowned painter in Kyoto. From1768 to 1782), his fame and skill were highly evaluated, and he was included in the *”Heian Jinbutsu Shi” along with Maruyama Ōkyo. The donated paintings were hung in the hōjō (residence of the abbot in the temple) of the Shōkoku-ji temple for the annual drying out of insects, and were open to the public and became a matter of public interest.

Unfortunately, 30 of the “Dōshoku Sai-e” paintings were donated to the Imperial Household Agency during the Meiji era due to the influence of the government’s policy of abolishing Buddhism and Shinto separation, in order to rescue struggling temples. As a result, the Shōkoku-ji temple received a certain amount of grant from the government. During the time Jakuchū worked on “Dōshoku Sai-e,” he completed 50 mural paintings for the Daishoin of the Rokuon-ji temple and a large work of folding screens for the Kagawa Konpira-gū shrine.

After the age of 52, he began producing prints such as “Jōkyōshu,” “Genpo Yōka,” “Sokenjō,” and “colour print of flowers and birds.” In his later years, he energetically produced a series of notable works that have been passed down to future generations, such as the “Hakuzō Gunjū-zu” and “Ju Kachōjū-zu Byōbu” screens, “Saboten Gunkei-zu (Cactus and Fowls Painting)” and “Renchi-zu (Lotus Pond Painting)” of the Saifuku-ji Temple, “Chickens Pauinting” of the Kaihō-ji temple, and “Amaranthus tricolor and Praying Mantis”, “Scroll with Vegetables and Insects,” “Sekihō-ji Temple Paintng,” etc. Additionally, in his very last years, he painted the “Flowers” ceiling paintings at Sekihō-ji temple.

*”Heian Jinbutsu Shi”: Biographical directory and popularity ranking list of a comprehensive collection of cultural and intellectual figures living in Kyoto in the early modern period.