Imamura Shikō: A Revolutionary Who Broke down the Tradition of Japanese Painting

A Hawk

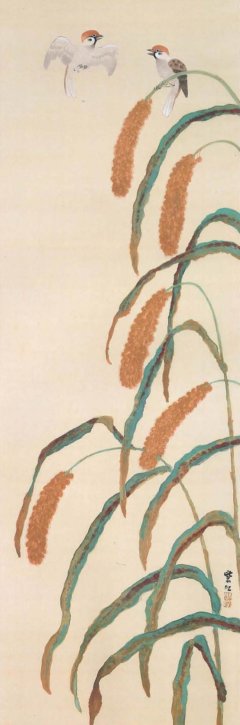

Millet

In 1910, Shikō was creating his work, “Preaching Dharma”, which he exhibited at the 10th Tatsumi Painting Exhibition. Finishing the rough sketch, Shikō was about to work on its rendition. Then out of the blue, Shikō cut the tip of the brush with scissors to near the root. Shikō inked that brush and rubbed it on the canvas dotting lines. Shikō also applied this technique to the coloring of his pieces. His method prevented lines from standing out too much and gave a powerful and beautiful impression on his works.

In his works after “Preaching Dharma”, Shikō often attempted at stippling and, in fact, this technique produced unique effects. One of its examples is his work, “A Hawk”. His work, “A Hawk”, was painted in black ink alone. Nonetheless, the gradation of shading applied to hawk’s feathers is beautiful.

From around the end of the Meiji era, Shikō was gradually attracted to the free style of Nanga painting. However, his interest costed him much. Shikō had to broke with one of his closest friends, Yasuda Yukihiko. Holding a strong trust mutually, Yasuda and Shikō had been working together in their creative activities. However, to master their own style, they dissolved Kōjikai, a research group of Japanese-style painters of the Yamato-e style. They, of course, reached this conclusion after understanding other’s opinion very well. In Shikō’s piece, “Millet”, there are some hints that suggest his devotion to Nanga style painting. Shikō freely and spontaneously painted a few stalks of millet laden with ears hanging down and two sparrows on top of them while boldly using colors.

Imamura Shikō was born in Yokohama and after graduating from elementary school, he learned watercolor painting from Yamada Basuke. In 1897, counting on his older brother, Shikō went to Tokyo and became a disciple of Matsumoto Fūko. There, Shikō studied Japanese painting. Shikō made a quick leap with his apprenticeship. In the fall of the following year, Shikō, for the first time, got his painting accepted for the exhibition hosted by the Japan Art Society. Later, Shikō continued exhibiting his pieces at various expositions. In 1900, Shikō came to know Yasuda Yukihiko and entered Shikōkai. This group, Shikōkai, was later renamed Kōjikai.

Kōjikai lasted until it celebrated its 19th exhibition in 1913. Meanwhile, its registered painters such as Yasuda Yukihiko, Ushida Keison, Hayami Gyoshū, Kobayashi Kokei, and Maeda Seison made ambitious productions while competing with each other. And Shikō strongly led them all. In 1912, at the 6th Bunten exhibition, Shikō, using bold color scheme and composition, created his own “Eight Views of Ōmi”. Scenic views of Ōmi Province was a popular subject matter for painting and there were traditional patterns already established for this theme. But in Shikō’s version, the Impressionism is brilliantly brought to life in Japanese painting. Back then, two leading figures of Japanese painting, Yokoyama Taikan, and Hishida Shunsō, were extremely influential in the evolution of the Japanese Painting technique. And Shikō’s “Eight Views of Ōmi” helped them promote the modernization of Japanese painting. From around that time, Shikō gradually became attracted to the free style of Nanga painting. By 1913, Kōjikai had cultivated its own tendency for painting, which Shikō could not follow. Therefore, Shikō dissolved it and in the following year, he traveled to India. Returning to Japan, Shikō exhibited his work, “Sceneries in the Tropical Land (Scroll of Morning/ Scroll of Evening), at the 1st exhibition of the Revived Japan Art Institute. And his work caught much attention. In this piece, Shikō’s unique painting independent of any other style is at play. At the end of that year, Hayami Gyoshū, Omoda Seiju, and Nakamura Gakuryō, led by Shikō, formed Sekiyōkai. And Shikō was more passionate about bringing innovation to Japanese art. But the painting style of Shikō began to take on a new aspect that can be called Shin-Nanga, an integration of Impressionism and Nanga. But, in 1916, the development of Shin-Nanga style was suddenly suspended due to Shikō’s death. Shikō died at the age of just 37.