Kanō School / Kanōha Group History | Japanese Painting School Information

The Kanōha group is the largest gaha (group of painters) in Japanese art history, and was active for about 400 years from the middle of the Muromachi period (15th century) to the end of the Edo period (19th century) as a group of expert painters that consistently dominated the art world. Kanō Masanobu, the official painter of the Muromachi shogunate, was the earliest ancestor; his descendants worked for Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and the Tokugawa Shogun as painters after the collapse of the Muromachi shogunate, consistently dominating the art world associated with the powers-that-be, thus greatly influencing Japanese art circles as a professional painter group working on works ranging from screen paintings in the Imperial Palace, castles or large temples to small paintings such as those created on fans.

Contents

Summary

The Kanōha group is a painter group mainly concerned with consanguinity such as parents or brothers; it reigned over the nation’s realm of art for as long as four centuries, a period unequaled anywhere in the world.

Prominent painters of the Kanōha group include the founder Kanō Masanobu, who worked for Ashikaga Yoshimasa, the eighth Seii taishōgun (literally, “great general who subdues the barbarians”) of the Muromachi shogunate; his heir, Kanō Motonobu, a grandson of Motonobu; Kanō Eitoku (狩野永徳), who created screen paintings of the Azuchi and Ōsaka castles; a grandson of Eitoku, Kanō Tan-yū, who moved from Kyōto to Edo and supervised the creation of screen paintings of Edo Castle and Nijō Castle; Kanō Sanraku, who stayed in Kyōto, thus representing a group called ‘Kyō Kanō.’

Once the structure of the Edo shogunate had become stable, the members of the Kanōha group were driven to get extensive orders done for screen paintings of the Imperial Palace and castles as the shogunate’s official painters. In order to fulfill large numbers of orders for screen paintings, the head of the Kanō family needed to lead the painters so they could work in a group. Consequently, the painters of the Kanōha group needed to learn ancestral painting examples and ways of painting without expressing their individuality as painters. Given such an historical backdrop, it can be said that the Kanōha group after Kanō Tan-yū only tried to keep the tradition and maintain influence as official painters, and therefore lost its artistic drive.

In the present day, an artist’s expression of individuality and mentality is valued, so the evaluation of paintings of the Kanōha group is not necessarily high. However, it is a fact that the Kanōha group led the Japanese art world for about four centuries and that numbers of painters were developed by the group; thus one can hardly discuss the history of Japanese painting but exclude the Kanōha group, whether in positive or negative terms. It is also a fact that many Japanese painters after the early years of the modern age were influenced by the Kanōha group and started with the influence of the Kanōha group; initially, Ogata Kōrin, of the Rinpa group, and Maruyama ŌKyo had learned from the Kanōha group.

Muromachi Period (1336 – 1573)

Kanō Masanobu

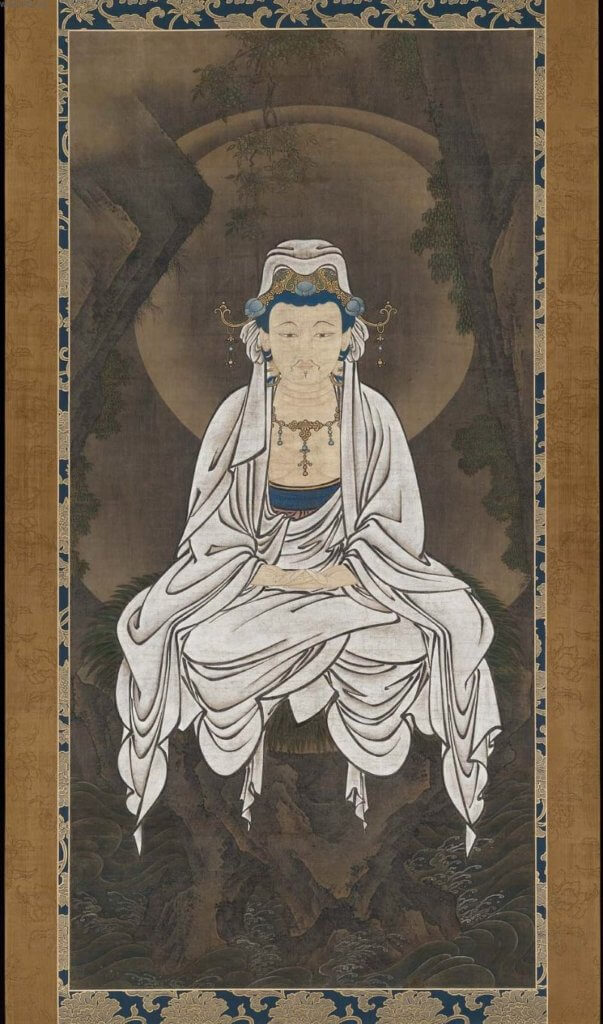

The Kanōha group was founded by Kanō Masanobu (c. 1434 – 1530), who worked as the official painter for the Muromachi shogunate. He lived quite long for a Japanese of the time (it is commonly believed that he died at age 97), and worked from the middle of the fifteenth century until the early sixteenth century. He was born in Kazusa province (present Chiba prefecture). Due to the progress of study after the late twentieth century, it is speculated that the Kanō family was somehow related to the Nagao clan in Ashikaga, Shimotsuke province (present Ashikaga city, Tochigi prefecture); and “Waterfall,” an ink painting that remains at Chōrin-ji temple in Ashikaga city, is considered a relatively early work by Masanobu. The first painting work recorded as having been done by Masanobu is the screen paintings he did of the Deity of Mercy and Luohan in Unchōin, a sub-temple of the Shōkoku-ji temple, which he did in Kyōto at the age of 30 in 1463. This was just before the turmoil of the Onin War (1467 – 1477) (as reported in Inryoken Nichiroku (Inryōken’s Diary)), which tells us that Masanobu was already working as a painter in Kyōto by that time. The Shōkoku-ji temple, as the main temple building of Unchōin, where Masanobu created the screen paintings, is a zen temple constructed by Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, the third Shogun of the Muromachi shogunate; it is the heart of the Muromachi art world, which produced artist-monks such as Josetsu, Shūbun, Sesshū Tōyō; moreover, in those days Oguri Sōtan (1413 – 1481), an artist-monk who was a disciple of Shūbun, worked as an official painter. Although it is not exactly certain when Kanō Masanobu went to Kyōto, whom he studied under and when he became the official painter for the Muromachi shogunate, it is clear (according to certain records) that Ashikaga Yoshimasa, the eighth Shogun of the Muromachi shogunate, gave him an important position. In 1481, a few years after the tumultuous Ōnin War (1467 – 1477), which had lasted for a decade, Sōtan, the official painter for the Muromachi shogunate, died; thus it is thought that Kanō Masanobu was appointed as the official painter for the shogunate, succeeding Sōtan. Subsequently, Tosa Mitsunobu, of the Yamatoe group (a style of Japanese painting) who was in the postion of Edokoro-azukari (a leader of painters who worked for the Imperial Court) of the Imperial Court, and Kanō Masanobu of the Kanga (a Chinese style of painting) group, became two major forces in the art world.

In 1482, the former Shogun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, started the construction of Higashiyama dono (the predecessor of Ginkaku-ji temple), and Masanobu took charge of the screen paintings. Following the death of Yoshimasa in 1490, Masanobu worked for the Hosokawa clan, which had political power at the time. In this way Masanobu solidified his position in the art world while deepening his relationship with the powers-that-be, and built a foundation for the subsequent prosperity of the Kanōha group. According to records, it is known that Masanobu created works in various styles and subjects, including screen paintings and Buddhist paintings; however, all his screen paintings have been lost and the existing works are limited to small paintings such as a hanging scroll. His painting style was ‘kanga,’ with ink painting based on the brushwork of Sung and Yuan in China, in contrast to the traditional Yamatoe of his contemporary, Tosa Mitsunobu.

Kanō Motonobu

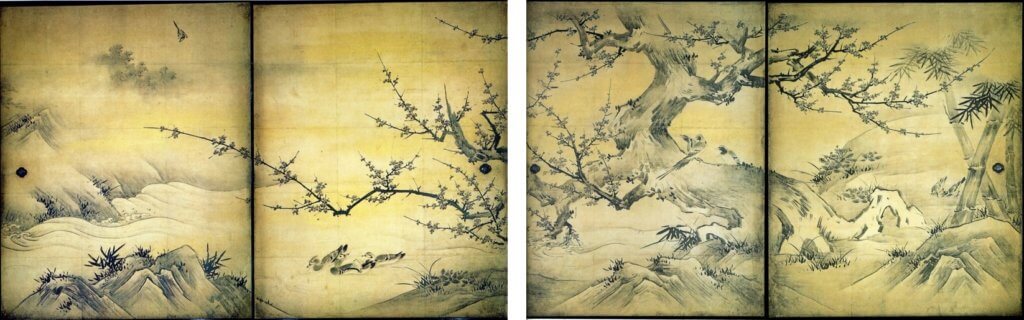

The second generation, Kanō Motonobu (1476-1559), who built the basis of prosperity of the Kanōha group, was the heir of Masanobu. His best existing works include the screen paintings in the hōjō (chief priest’s room) of the Daisen-in, a sub-temple of the Daitoku-ji temple (the hōjō was completed in 1513) and another one in the Reiun-in, a sub-temple of the Myōshin-ji temple in 1543 (it is widely believed that the screen paintings in the Daisenin were not created at the time when the hōjō was completed but were done in a slightly later period). The creation of the screen paintings in the hōjō of the Daisen-in was divided among Sōami, Motonobu and his brother Kanō Yukinobu, depending on the room; accordingly, Motonobu took charge of “Four Seasons, Flowers and Birds” in ‘Danna no Ma’ and “Founder of the zen sect” in ‘Ihatsu no Ma.’

“Founder of zen sect” is a typical ink painting, while “Four Seasons, Flowers and Birds” is based on ink and shows a new flavor at the same time, as it uses colors only on the flowers and birds. Motonobu strengthened the ties with the Ashikaga Shōgun and the Hosokawa clan as the powers-that-be, had numerous disciples and consolidated the basis of the Kanōha as a group of painters.

Because Motonobu referred to himself as ‘Echizen no kami’ in his later life, he was given a priestly rank called ‘Hōgen’ however, for posterity he has been referred to as ‘Ko Hōgen’ or ‘Echizen Hōgen.’ The work is wide-ranging: he created the Engi Emaki of temples and shrines, votive pictures, gilded folding screens in the Yamatoe style, and portraits as well as screen paintings. Motonobu assumed the Yamatoe painting style in Kanga and ink painting (in which his father Masanobu specialized); he specialized in large decorative paintings such as a Fusuma (Japanese sliding door) and a folding screen, and built a foundation for the style of the Kanōha group. He is also called the founder of the early modern screen paintings as he established the concept of painting styles such as Shintai (standard style), Gyōtai (semi-cursive style), and Sōtai (cursive style).

Azuchi-Momoyama Period (1573–1603)

Motonobu had three sons: Munenobu, Hideyori and Naonobu; Naonobu (1519-1592); the first, Munenobu, died young, and the third son Naonobu succeeded as the head of family. It is not clear why their family estate was transferred to the third son Naonobu instead of Hideyori, the second son. Naonobu is widely known as Kanō Shōei (his posthumous name), and he was active from the Muromachi period to the Momoyama period. The huge “Nirvana” (six meters long) in the Daitoku-ji temple is his finest work. Although he participated in the creation of the screen paintings for the Ishiyama Hongan-ji temple with his father Motonobu as well as in the creation of the screen paintings for the Jukōin, a sub-temple of the Daitoku-ji temple with his son Eitoku, he was a less famous artist because his father Motonobu and his son Eitoku were more prominent.

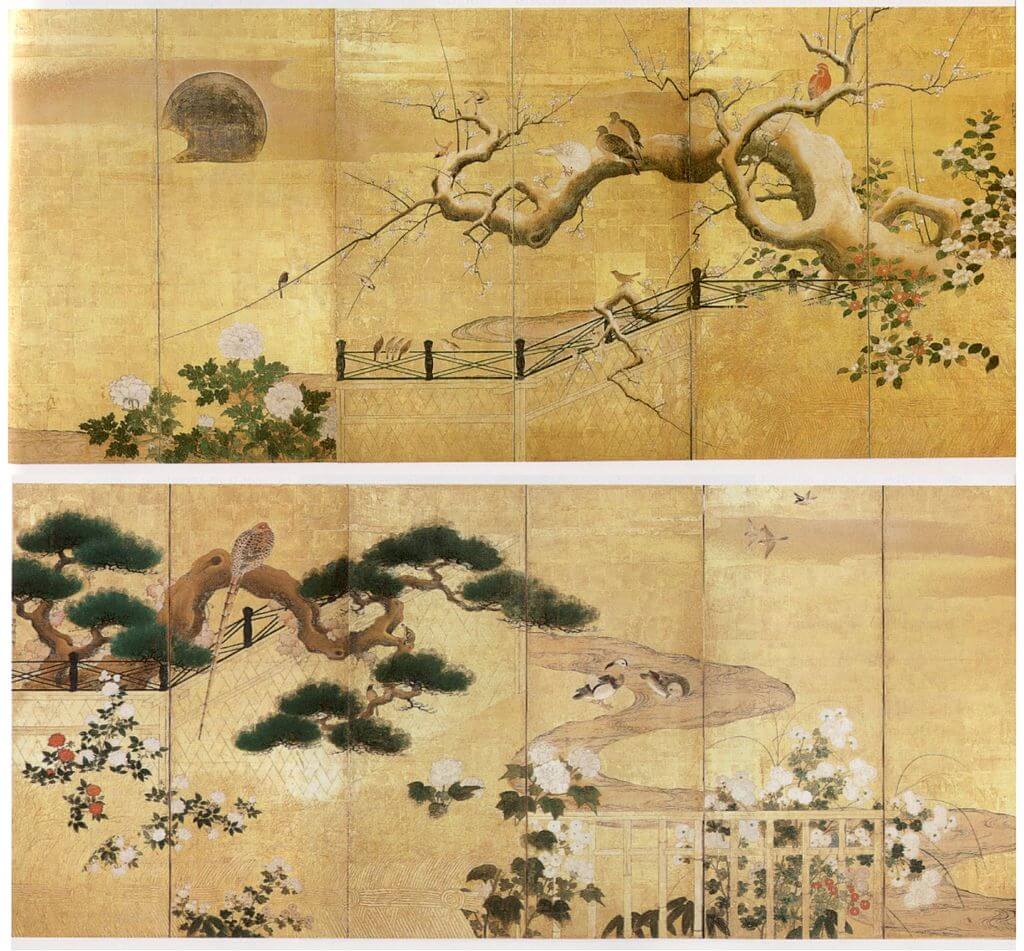

Kanō Eitoku (狩野永徳) (1543-1590), the heir of Shōei, is also called Kuninobu; he is one of the most distinguished painters of the Japanese art world from the Momoyama period. Although he created numbers of screen paintings in strict compliance with the plans of the men in power who had survived wild times–including Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi–these paintings were lost with the buildings, so relatively few of Eitoku’s works remain in existence. The paintings on the partitions in the hōjō of the Jukōin, the Daitoku-ji temple (which are among his best existing works) were created by Eitoku together with his father Shōei; however, Shōei had Eitoku take charge of Fusumae of the major room in the south front of the hōjō, while he took a supporting role. In the days of feudal society it was a common practice that the head of a family would create Fusumae in the major room, so it is historically believed that, at the time such paintings were created, Shōei had already retired after transferring the family estate to Eitoku, who was a great talent. “Flowers and Birds” in Shitchu (the center front room of the Hōjo) is very highly acclaimed among the screen paintings of Hōjō of Jukōin.

Subsequently, Eitoku became involved in the creation of the screen paintings in Azuchi Castle Tower, which Oda Nobunaga constructed during the period from 1576 to 1579. He created screen paintings in the Ōsaka Castle of Toyotomi Hideyoshi and the Jurakudai after Nobunaga died, and in his later years also became involved in creating the screen paintings in the Imperial Palace. As Eitoku’s existing best works, the screen paintings in the hōjō of the Jukōin, as previously described, are renowned as well as “Foo dogs, folding screen” as former imperial property, and “Urban and suburb of Kyōto, folding screen,” as handed down through the Uesugi clan; it has also been said that “Cypress, folding screen” in the Tōkyō National Museum was painted by Eitoku. Eitoku excelled at elaborate paintings and monumental paintings, although he had no choice but to paint in the monumental painting style in order to fill a large number of orders for screen paintings. An elaborate painting is interpreted as a work described in every detail, and monumental painting is interpreted as having a high-minded style.

The Kanōha group also had the most important painters in the early modern ages. “Viewing Maple Leaves in Takao,” a designated national treasure, has the seal of ‘Hideyori’; it has been said that this was painted by Kanō Hideyori (birth and death dates unknown), the second son of Kanō Motonobu; however, it is also said that this ‘Hideyori’ of “Viewing Maple Leaves in Takao” is another painter called Shinshō Hideyori, a grandson of Motonobu. Kanō Sōshū (1551 1601) was a brother of Eitoku, also called Motohide, and worked as an assistant to Eitoku in the creation of the screen paintings in Azuchi Castle. Folding screens and portraits still in existence have been attributed to him. Kanō Naganobu (1577-1654), another brother of Eitoku, is renowned as the painter of “Playing Under the Flowering Trees,” a national treasure. As painters other than the direct line of the Kanō family, Kanō Yoshinobu (1552-1640), who painted “Craftspeople, folding screen” in Kawagoe Kitain, and Kanō Naizen (1570-1616), who painted “Hōkoku Festival, folding screen” in Kyōto Toyokuni-jinja Shrine (Kyōto city), are well known.

The early Edo period

* Edo Period: 1603–1868

Kanō Eitoku (狩野永徳) died at age 48, preceding his father Shōei (Naonobu). Eitoku’s first son Kanō Mitsunobu (c. 1565-1608) and second son TaKanōbu Kanō (1571-1618) succeeded him. Mitsunobu created the screen paintings in the Reception Hall of the Kangaku-in, a sub-temple of the Onjō-ji temple; in contrast to Eitoku he specialized in delicate painting in the Yamatoe style. Such a style of painting might not have suited the public taste at the time, and the early modern essays on paintings, including “Honchōgashi,” generally put a low value on Mitsunobu.

After the death of the Kanō family head Mitsunobu, his brother Takanobu led the Kanōha group because his son Kanō Sadanobu (1597-1623) was only 12 years of age. Under the feudal system, the family line of Sadanobu, Mitsunobu’s first son, was supposed to be the head of family; however, Sadanobu died without an heir at the age of just 27, so after that the legitimacy of the Kanō family was the descendant of Takanobu till the end of the Edo period. Takanobu had three sons–Morinobu (Kanō Tan-yū 1602 1674), Kanō Naonobu (1607-1650) and Kanō Yasunobu (1613-1685)–and they respectively became the earliest ancestor of the Kajibashi Kanō family, Kobikichō Kanō family and Nakabashi Kanō family. Although the youngest son, Yasunobu, succeeded as the Kanō head of family as an adopted son of Sadanobu (mentioned above), the most renowned painter was Morinobu (also known as Tan-yū).

Morinobu later became a priest and called himself Tan-yūsai; as a painter he is known as Kanō Tan-yū. He eventually moved to Edo and solidified the position of the Kanōha group in the art world more as the official painter of the Edo shogunate.

Tan-yū exercised his painting talent from childhood; in 1612, he met Tokugawa Ieyasu in Sunpu at the age of 11 and obtained a residence in Edo Kajibashi Mongai in 1621, subsequent to which he worked based in Edo and energetically created screen paintings in castles and large temples.

Among Tan-yū’s works, the screen paintings in the Edo and Ōsaka castles were lost with the buildings, but the screen paintings (ink paintings) in Jōrakuden of Nagoya Castle are existent, having avoided an air raid during World War II because they had been removed from the building and evacuated; additionally, the screen paintings in Ninomaru Palace of Nijō Castle and the hōjō of the Daitoku-ji temple are among his best existent works. He created various kinds of works, including hanging rolls, picture scrolls and folding screens, as well as these large paintings. He created the screen paintings in the Ninomaru Palace of the Nijō Castle when he was young (25 years of age), and they showed dynamism in Eitoku’s style; however, the screen paintings in the Daitoku-ji temple, which he created later in his life (mainly with ink and water), display a calm approach with abundant use of blank space. He had works in the Yamatoe style in picture scrolls and folding screens as well.

Tan-yū emphasized sketches and the copying of ancient paintings; consequently, he left numerous sketch books and reproduction books. Many of Tan-yū’s copies of ancient paintings (called ‘Tan-yū Reduction’) are existent, which are now part of museums and collections around the nation, and they include many copies of ancient paintings whose originals are now lost, so they are valuable as data for the study of Japanese art history.

From the Mid-Edo Period

The Kanōha group during the Edo period was a huge painting group comprised of a consanguinity group mainly with the head family of the Kanō family and numerous disciples around the nation, thus comprising a hierarchy. They are clearly ranked: under the most prestigious four families (called ‘oku-eshi inner court painters’) there are about 15 families less prestigious called ‘omote-eshi outer court painters’ and then the ‘Machi Kanō painters’ who catered to the demands of townspeople instead of the Imperial Court or temples and shrines; and consequently their influence spread throughout the nation. The powers of the time sought the stability and continuity of feudal society, and the paintings for public places such as Edo Castle were supposed to be painted in the style of traditional painting examples; they were not intended to be unique. In order to create numbers of screen paintings, one must work in a group with all the disciples; therefore, in order to make group work easier, the ability to learn from painting examples was valued more than one’s individuality as a painter. In this respect it is undeniable that the paintings of the Kanōha group lack individuality and originality.

It is said that the oku-eshi inner court painters ranked with Hatamoto and were allowed ‘audience’ with the Shōgun as well as belting on a sword, which implies a high status. The four families of the oku-eshi are the Kajibashi family, with lineage of Tan-yū (the first son of Kanō Takanobu); the Kobikichō family (called Takekawa-chō family at the time), with lineage of Naonobu (the second son of Takanobu); the Nakabashi family with lineage of Yasunobu (the third son of Takanobu); and the Hamachō family, with lineage of Kanō Minenobu (1662 – 1708) (Minenobu is the second son of Kanō Tsunenobu, the first son of Kanō Naonobu). Tan-yū adopted Tōun (Kanō Masunobu, 1625-1694), the son of Gotō Ryūjō, a swordsmith because he had no child. Later, Kanō Morimasa (1653-1718) who was his biological son (born after Tan-yū turned 50) succeeded him, but subsequently this lineage had no distinguished painter. Among the numerous disciples of Tan-yū, Kusumi Morikage (birth and death dates unknown), the creator of “Enjoying the Cool of the Evening Under the Moonflower Trellis,” is renowned. Morikage was for some reason expelled from the Kanōha group; he worked in the Kanazawa area later, but his records aren’t completely clear.

As stated previously, the head family of Kanō was succeeded by the Nakabashi family of Yasunobu, a brother of Tan-yū. Kanō Tokinobu (1642-1678), a son of Yasunobu, died in his thirties, and his son Kanō Ujinobu (1675-1724) succeeded the family estate; however, subsequently this lineage had no distinguished painter. Hanabusa Icchō (英一蝶) (1652-1724), who was popular based on his sophisticated painting style, was a disciple of Yasunobu. The family that produced relatively prominent painters until the end of the Edo period among the four families of the inner court painters is the Kobikichō family, of Naonobu’s lineage. This family line produced Kanō Tsunenobu (1636-1713), the heir of Naonobu, and Tsunenobu’s sons, Kanō Chikanobu (1660-1728) and Kanō Minenobu (1662-1708). Minenobu won the favor of the Shogun Tokugawa Ienobu, and he later gained independence as ‘Hamachō family,’ which was ranked as one of the inner court painter families. Besides them, Kanō Kōi (date of birth unknown – 1636) was not related by blood to the Kanō family but, along with his brothers, was a master of Tan-yū; he was allowed to use the surname of Kanō due to his achievements, and he worked for the Kishū Tokugawa family.

Meanwhile, a group called ‘Kyō Kanō’ remained active in Kyōto, and Kanō Sanraku (1559-1635), a disciple of Kanō Eitoku (狩野永徳), was the pillar of the group. Sanraku was from the Kimura clan in Ōmi, the vassal of Toyotomi Hideyoshi; his original name was Kimura Mitsuyori. His best works are “Peonies” and “Red and White Plum Trees” in the main house of Kyōto Daikaku-ji temple, and they have colorful and decorative pictures on a golden base. Kanō Sansetsu (1589/90-1651), the husband of Sanraku’s daughter, created the screen paintings in Tenkyūin, MyŌshin-ji temple as well as some paintings of folding screens, which are still in existence. He had a distinctive painting style unique among painters of the Kanōha group, such as distinct shapes of trees and rocks, as well as the completeness of detail. The essay on paintings made by Sansetsu and edited by his son Kanō Einō (1631-1697) is entitled “Honchōgashi,” the first full-fledge painting history book by a Japanese.

The Kobikichō family produced Kanō Michinobu (Kanō Eisen-in Michinobu (1730-1790)), Kanō Korenobu (Kanō Yōsen-in Korenobu (1753-1808)), Kanō Naganobu (Kanō Isen-in Naganobu (1775-1828)) and Kanō Osanobu (Kanō Seisen-in Osanobu (1786-1846)) during the late Edo period. Kanō Seisen-in Osanobu led the creation of numerous screen paintings as a master of the Kanōha group during the reconstruction of the Nishinomaru and Honmaru palaces of Edo Castle, which had burned down in 1838 and again in 1844. Although the paintings are no longer in existence, numerous designs are in the possession of the Tōkyō National Museum. Kanō Seisen-in Osanobu also endeavored to copy and collect ancient paintings. Although the painters of the Kanōha group in the late Edo period are not well appreciated generally, there is a move to reappraise Kanō Seisen-in Osanobu as the progress of the study after the late twentieth century recognizes that he was a painter with good technique who eagerly studied art from ancient paintings and on to the new painting movement at the end of the Edo period.

Kanō Hōgai (born in Shimonoseki, 1828-1888), a leading figure of the Japanese art world during the early Meiji period, like Hashimoto Gahō (born in Kawagoe, 1835-1908), was a disciple of Kanō Tadanobu (Kanō Shōsen-in Tadanobu 1823-1880), the next generation of Seisen-in. Both Hōgai and Gahō were from painter families of the Kanōha group. The historical role of the Kanōha group as a professional painter group finished as its patron, the Edo shogunate, ended.