Kitagawa Utamaro: The Master of Bijin-ga of Ukiyo-e Who Fought Against the Regulations of the Shogunate

When you talk about Bijin-ga (beautiful woman paintings), you must think about ” Kitagawa Utamaro”. He is a well-known Ukiyo-e artist along with “Katsushika Hokusai” in overseas, and of course highly evaluated in Japan. However, his artistic activity was also a fight against the prohibition of the Shogunate. We will be introducing the turbulent life of Kitagawa Utamaro.

The Life of Kitagawa Utamaro

The Birth, Childhood, and Family

Despite being a well-known Ukiyo-e artist, there are few documents and historical materials about Kitagawa Utamaro’s birth, and details about his birth or his family line have not yet been clarified, but this is a common thing among Ukiyo-e artists.

The year of birth is 1753, which could be calculated back from the year of his death (at 54 years old). Although the theory that the place of birth was Edo is predominant, there are various theories such as Kyoto, Tochigi, and Kawagoe, but there is no confirmation of any of them.

Information about the family is also not very clear, and there are documents saying he had a wife, but there are also records saying the opposite.

Kitagawa Utamaro began his training in painting under the Kanō school painter “Toriyama Sekien”.

Toriyama Sekien is a painter known for drawing many Yōkai-ga (painting about Japanese monsters). At that time, he had many disciples, and other than Kitagawa Utamaro, and also had “Koikawa Harumachi” and “Eishōsai Chōki” as his disciple.

Kitagawa Utamaro, who is said to be a master of Bijin-ga, also drew Yakusha-e (actor paintings) in the early days, like many Ukiyo-e artists.

In 1781, Kitagawa Utamaro drew illustrations for Kibyōshi (a pictorial entertainment book published in Edo from the middle of the Edo period) of Tsutaya. This work was the first work with Tsutaya Jūzaburō who later had a close relationship, and at the same time, it became the first work by the name of “Utamaro”.

It is said that he had settled in the area around Ueno and Nezu at that time, but soon he moved to Tsutaya Jūzaburō’s house.

Tsutaya Jūzaburō was a publisher representing the Edo period and was active as a publishing producer.

The place his birth was Shin-Yoshiwara, where the yūkaku (a red-light district) was at. From around the mid-20s, he became an agent for Yoshiwara’s guidebook “Yoshiwara Saiken” and made money. Since then, he planned and published books and Nishiki-e one after another, and made great use of his foresight, which lead to his success in the publishing world.

Tsutaya Jūzaburō understood the talent of Kitagawa Utamaro, and from the Meiwa to Kansei period (1764-1801), he released hit works one after another together with Kitagawa Utamaro.

The reason why many prostitutes appear in Kitagawa Utamaro’s work and the style that captures the detailed gestures and facial expressions of women is because he was with Tsutaya Jūzaburō, who had a deep insight about Yoshiwara.

By the way, it can be seen that the works of this time were influenced by the fashionable Ukiyo-e artists of the time, such as “Kitao Shigemasa” and “Torii Kiyonaga”, and his own style of painting had not yet been seen.

Became Famous for Kyōka Picture Book during the Kansei Period

From 1767 to 1786, Tanuma Okitsugu was in control of government. A culture of enjoyment was spreading due to the policy of flourishing commerce and rebuilding the government’s finances.

Among them, “Kyōka” was especially popular. Kyōka is a Tanka with a stylish and satirical element. Around this time, there was even a “Kyōka Salon” where samurai and town people gathered in the galleries and teahouses to read Kyōka.

Tsutaya Jūzaburō understood the popularity and tries to contact the popular Kyōka master “Ōta Nanpo“.

Then, he introduced Kitagawa Utamaro to the Kyōka Salon where popular artists such as Ōta Nanpo gathered. With this as a trigger, Kitagawa Utamaro started to read Kyōka and became active in the illustrations of Kyōka picture books.

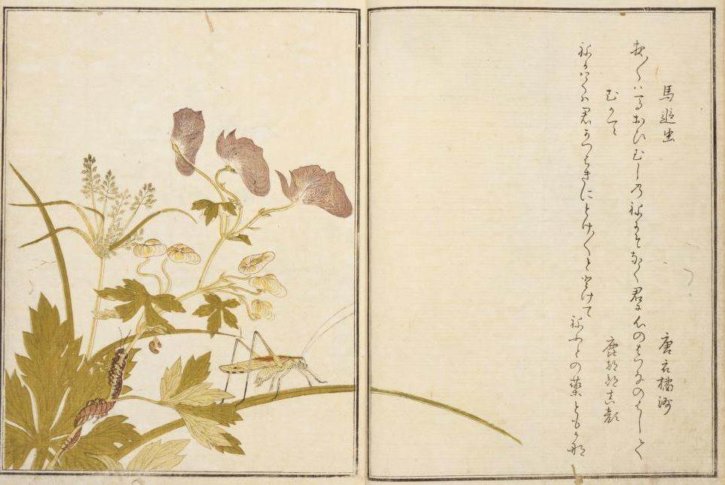

The first work in which Kitagawa Utamaro’s ability was highly evaluated was a Kyōka picture book called “Ehon Mushierami”.

It was in 1788 that “Ehon Mushierami ” was published. At the time, the administration had moved from Tanuma Okitsugu to Matsudaira Sadanobu.

It was around the time when the mood changed from an enjoyable mood to a simple mood, and the Kyōka boom was beginning to fade. Speaking of Kyōka event, prostitutes and Geisha were usually associated with it, but people had to refrain from luxury, and Kyōka event was unavoidably held with the theme of insect decency.

A Kyōka picture book was created by adding a painting of Kitagawa Utamaro to the Kyōka that was read there. Although “Ehon Mushierami” was based on insects, there were many glossy Kyōkas, and the delicate paintings drawn by Kitagawa Utamaro suited the Kyōka and have gained a good reputation. The different textures of insects and flowers, the use of colors, and the realistic expression are still highly regarded today. Tsutaya Jūzaburō, who felt a good feeling with the “Ehon Mushierami”, continued to ask Kitagawa Utamaro for many Kyōka picture books.

In the Kansei period, the shogunate’s regulations on luxury goods became stronger. This is the so-called “Kansei no Kaikaku (Kansei Reforms)”. In 1787, Matsudaira Sadanobu, 30 years old grandson of “Tokugawa Yoshimune“, became a rōjū (the highest work position in Edo government).

The young rōjū carried out reforms aimed to rebuild the shogunate system, purge regulations, and stop the chaos of starvation. The eyes of surveillance were also turned to the publisher, and some members of the Kyōka Salon were punished. The members who led the Kyōka salon disappeared from the salon one after another, and the Kyōka boom came to an end.

Kitagawa Utamaro and Tsutaya Jūzaburō sent out a “Shun-ga (erotic art or pornographic painting)” called “Utamakura” while the shogunate’s strict abstinence system prevented them from working in Kyōka picture books.

Since Shun-ga depicts sex customs, it was not something that was openly lined up in bookstores, but something that was subject to disposal if it was discovered by the Shogunate.

I’m not sure if Kitagawa Utamaro and Tsutaya Jūzaburō’s decision was a manifestation of a rebellious spirit, but it was a surprising move. In the early days of Kansei period, Kitagawa Utamaro had continuous suffering happenings.

In 1790, the Shogunate officially issued a publication control order, allowing only those that passed censorship to be published, and it was prohibited to express contemporary cases with Ukiyo-e or to make expensive books.

The following year, in 1791, a fashionable book published by Tsutaya Jūzaburō was censored and ordered to be not printed. The punishment was not limited to this, and Tsutaya Jūzaburō was sentenced to confiscate half of his property.

In response to this, Kitagawa Utamaro was notable to publish new works. In fact, there are no Kitagawa Utamaro’s works that are said to have been produced this year, and it was a year that we don’t know anything about.

Converting to Bijin-ga

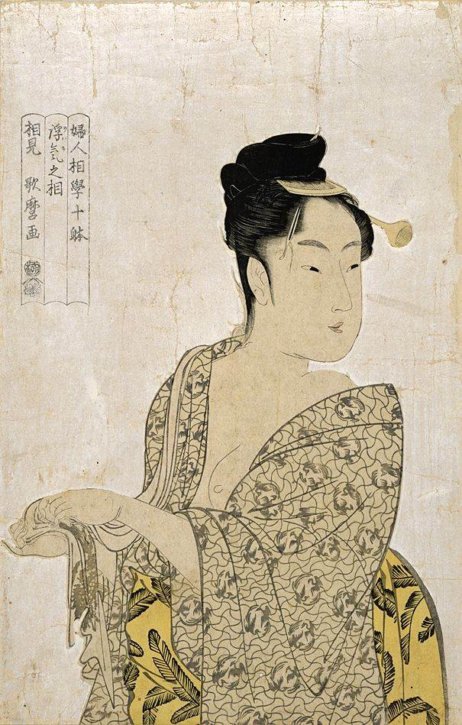

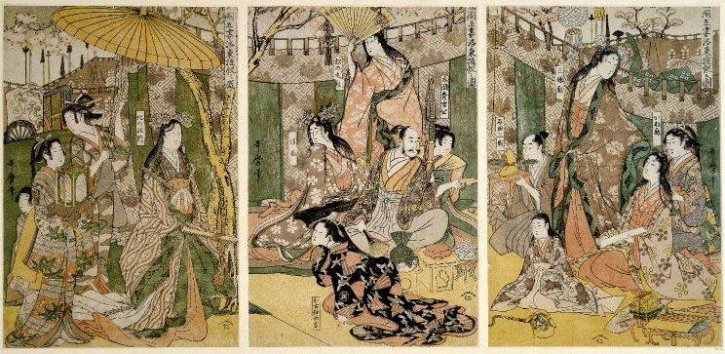

From around 1792, Kitagawa Utamaro began to focus on Nishiki-e, especially Bijin-ga (beautiful woman painting).

He had freed himself from the influence of Bijin-ga drawn by popular painters at the time such as Kitao Shigemasa and Torii Kiyonaga, and complete a unique style of his own painting that depicts a lustrous, fresh and expressive woman.

It was around this time that the Kitagawa Utamaro’s most famous masterpiece with composition which depicts the breast of women, called “Bijin Ōkubi-e” was born.

Bijin Ōkubie is a very ordinary composition nowadays, but at that time, Bijin-ga were all drawn in full-body images and landscapes, and there was almost no composition that focused on breast.

Drew a Woman More Realistically. Speaking of Bijin-ga, Kitagawa Utamaro’s Name Came Up at This Time.

Kitagawa Utamaro and Tsutaya Jūzaburō published Bijin Ōkubi-e works one after another such as “Kasen Koinobu”, which depicts a woman who is in love.

Among them, “Tōji Sanbijin” was a blockbuster. It is a painting of a real women who were said to be “the three most beautiful women of Kansei period”. In these works, even the features of the faces were drawn in detail, and it was also drawn with different painting feature depending on the person.

Even the Ukiyo-e artists who drew excellent Bijin-ga such as “Suzuki Harunobu” and Torii Kiyonaga, all drew with the same female face, and Kitagawa Utamaro’s method was revolutionary.

However, the new publication control ordinance of the Shogunate prevented this. It was forbidden to put names of geisha or teahouse girls in Bijin-ga.

Kitagawa Utamaro decided to counter this with “Hanji-e”

Hanji-e is a thing that infers words and answers from the painting, and it is a kind of mystery. He had the name of the drawn woman in a painting drawn.

These make us feel the rebellious spirit of Kitagawa Utamaro, who will not give in to the strict regulations from the Shogunate.

Throughout the Kansei period, he continued his creative activities energetically without giving in to the regulations of the Shogunate, and Kitagawa Utamaro established himself as an undisputed famous painter.

He produced one after another the works that are said to be the best masterpieces of his life.

Shogunate’s Regulations and Kitagawa Utamaro

Repeated Shogunate’s Regulations

Kitagawa Utamaro tried to escape the regulation by Hanji-e. However, in 1796, even Hanji-e was banned. After that, he released Nishiki-e with the theme of working women, and managed to stay in the position of a popular painter.

However, a ban is issued on the Ōkubi-e itself. The detailed facial expressions of women, which Kitagawa Utamaro was good at, can only be drawn with the composition of Ōkubi-e.

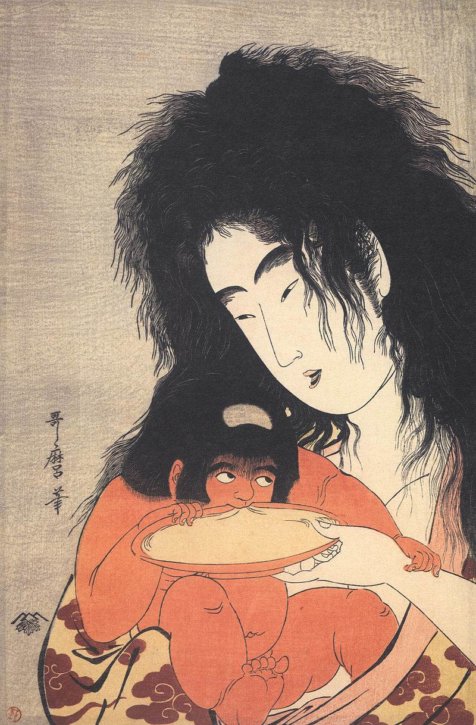

As the regulations were almost telling people not to draw, Kitagawa Utamaro was driven to corner too. Under such circumstances, Kitagawa Utamaro drew a series based on Japanese legends. There are more than 30 types of “Yama-uba and Kintarō” left. This work also has a devise, and he drew the Yama-uba, who originally should be an old woman, as a young mother so that people could feel its abundant charm. Kintarō, on the other hand, was drawn with an expression of the innocence of a child, and this was a work that conveys the charity of his mother.

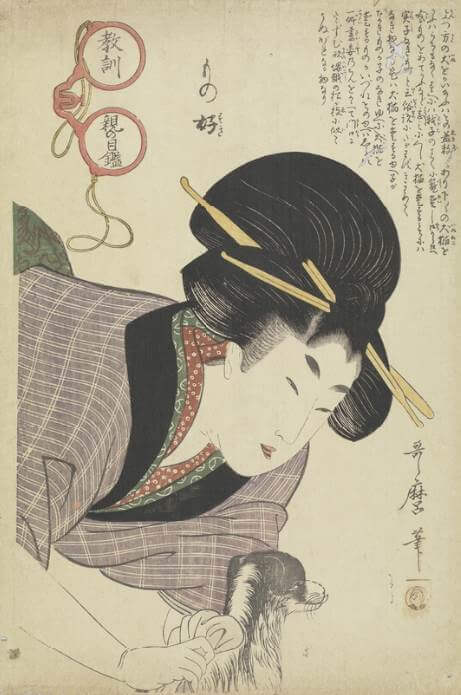

After that, Kitagawa Utamaro’s Bijin Ōkubi-e was decided to be published with “Kyōkun Oya no Mekagami”.

It was banned by the Shogunate, but as the title suggests, it was evaded by publishing it as a childcare lesson. By drawing a bad girl at that time and admonishing that “it should not be like this”, he showed a good response to the shogunate’s consciousness of simple and patience.

“Taikō Gosai Rakutō Yūkan no Zu” and Punishment

He continued to publish his work with a lot of ingenuity, but it is a fact that Kitagawa Utamaro started to lose his momentum from the time when he couldn’t freely draw town girls and beautiful Ōkubi-e.

Nevertheless, Kitagawa Utamaro had to continue drawing in order to live as a painter. As a result, his activities were always dangerous, crossing the line between the demands of the common people and the ban.

During this period, he also worked on Rekishi-ga (historical painting).

Published in 1797, “Ehon Taikōki”, which depicts the life of Toyotomi Hideyoshi with powerful illustrations, quickly became a bestseller.

With the wake of this “Taikōki” boom, Kitagawa Utamaro released a work depicting “Katō Kiyomasa” at the party when the troops were dispatched for Korea and a Musha-e (warrior painting) depicting “Shibata Katsuie” going to a war in 1804.

However, the Ukiyo-e “Taikō Gosai Rakutō Yūkan no Zu”, which was drawn in the same year based on Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s cherry blossom viewing, was strongly blamed, and the Shogunate punished him.

The work depicts Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who is surrounded by the “Kita no Mandokoro” and “Yodo-dono” and other concubines, drinking sake while viewing cherry blossom.

The shogunate argued that this painting was intended to ridicule the current shogun “Tokugawa Ienari”. However, Kitagawa Utamaro had no such intention, and it was a surprising punishment.

Kitagawa Utamaro was shocked by the fact that it was not the Bijin Ōkubi-e, which he had been fighting with against the ban, that was punished but it was the Rekishi-ga. Many people were sentenced to the arrest at this time.

In addition to Ukiyo-e artists “Katsukawa Shuntei” who drew Ukiyo-e with the theme of “Ehon Taikōki”, “Utagawa Toyokuni I”, the Gesaku artist “Jippensha Ikku” were also punished.

In addition, each publisher was ordered to have the printed materials confiscated and pay a fine. Furthermore, the regulation extends to the original “Ehon Taikōki”, and it was banned to be sold.

Kitagawa Utamaro in His Later Years

Kitagawa Utamaro, who had evaded numerous publishing controls, was weakened both physically and mentally after being punished by the Shogunate.

He was over 50 years old, and his rebellious spirit has finally died, and the painting wasn’t as clear as it used to be. The number of drawings based on classical figures and annual events had increased, and the challenges of the past were not seen.

In the end, it was whispered that “his future is not long”, but when the publishers found out that Kitagawa Utamaro would unlikely recover from his illness, they actively requested Kitagawa Utamaro to do the last work with them.

He didn’t fold the stop painting until he died, and occasionally left behind energetic works with satirical themes.

In 1806, Kitagawa Utamaro died at the age of 54.