Summary | Art History of Japan | Painting | No.3 Meiji Period

Meiji Period

Yes, the long Edo Period is over and the Meiji Period is next.

The period from 1868 to 1912 was characterized by “the Dawn of a New Japanese Painting”. I think it comes down to this.

You may say, ‘Wait. What do you mean by Japanese paintings? Aren’t the ones we’ve seen so far Japanese paintings too?’

But the term ” Japanese painting” is a very sensitive term in the history of Japanese art.

The concept of “Japanese painting” itself did not exist in Japan until the Meiji era.

In the Meiji era (1868-1912), Western paintings were introduced from the West. In order to compete with them, Japanese painters had to rethink and define what their own Japanese paintings had been until then. The term was born out of this process.

Until then, small factions and genres existed in Japan, and there was mutual recognition of these differences, but no such awareness of identity as Japanese paintings compared to foreign paintings had been formed.

For example,

Westerner: What is your painting?

Japanese painter A: What? It’s a painting of the Kanō school, yeah, Kanō school.

W: What is a Kanō School painting? Do you mean Japanese paintings?

J: Japanese painting? What’s that? The Kanō school is the Kanō school.

W: OK. Thank you, I can’t get through to him. Let’s hear from somebody else. What is your painting?

Japanese painter B: Wow, this is ukiyo-e.

W: Is this a Japanese painting?

J: What’s that? I don’t know. Never thought about that. It’s important to sell.

W: Oh my god. Where are the Japanese paintings? I think it was something like this.

Therefore, there are cases in which Japanese paintings up to the Edo period are included in the broad framework of Japanese paintings, and there are cases in which paintings created after the Meiji period are considered to be Japanese paintings, making ‘Japanese painting’ a sensitive term with very subtle differences in usage.

OK. Let’s take a look at what happened at the dawn of Japanese painting in the Meiji period.

First, the Black Ships came to Japan, then the Edo Shogunate opened the country, and then the Edo Shogunate disappeared and the Meiji Restoration took place. What happened as a result of this was a very difficult situation for painters.

Yes, painters suffered greatly in the early Meiji Era because of the drastic changes in the environment.

The following is a summary of the triple suffering of painters due to the Meiji Restoration.

The first is that the patron disappeared.

During the Edo period (1603-1867), under the shogunate and domain system, many painters were employed by their domains as “official painters”. They were paid a salary. However, in the Meiji Era, the shogunate and domain system was abolished, and all such people were dismissed from their jobs.

Well, it’s like the company went bankrupt.

The new company, the Meiji government, which was built on the site of the bankrupt company, did not hire me like before, and said, “We are going to operate under a different system, so we cannot hire you like the Edo shogunate. Goodbye”

So many painters lost their patrons and were forced to quit their jobs due to poverty. In other words, they had to change jobs. That was one of the first hardships.

The second hardship was the decline in the value of Japanese culture due to westernisation.

Western culture came to Japan and the Japanese got too excited about the following.

“Western is awesome after all! Civilisation, yay!”

As a result, Japanese culture was no longer looked at and the value of Japanese culture dropped. So, Japanese painters had to suffer because they could no longer make a living by painting Japanese pictures.

The third hardship was the movement to abolish Buddhism.

What is the movement to abolish Buddhism?

This movement is worth checking out as it had the greatest impact on Japanese art and Buddhism in the early Meiji period.

Let’s look at this in a little more detail.

The Meiji government issued a decree on the separation of Shintoism and Buddhism.

First, in 1868, the new Meiji government adopted the policy of nationalising Shintoism in order to realise the ideals of ‘Restoration of the Imperial Sovereignty’ and ‘Theocracy’, and issued a decree separating Shintoism and Buddhism in order to prohibit the previously widespread practice of mixture of Shinto and Buddhism.

I’ll explain this one more time in slightly different words.

Until then, Shintoism and Buddhism had been mixed together in Japan, but the Meiji Government decided that it would be better to separate them in order to promote politics mainly through the Emperor, who was regarded as a descendant of the gods in Japanese mythology, and issued a decree separating Shinto and Buddhist religions.

But unfortunately, this Shinto separation decree was completely misunderstood and passed on to the people.

The Japanese people felt that Buddhism was no longer necessary because Japan was going to adopt Shintoism, and Buddhism in Japan became a very marginalised religion.

And this anti-Buddhist movement became more and more radical.

There were various incidents, such as Buddhist statues in temples being destroyed and hanging scrolls of Buddhist paintings being burnt.

Thus, the early Meiji period was a very difficult time for Japanese-style painters, who had a very difficult time making a living.

As a result of these developments, the value of Japanese art has declined to the point where more and more Japanese art was exported abroad.

However, as expected, Japanese people started to realise that it would be bad for their own culture if it were to fall into disrepair.

So in 1878, an association called the Ryūchikai was created.

This was a group of key government officials that was formed to protect Japanese culture.

Then, a man named Ernest Fenollosa joined the Ryūchikai.

This Ernest Fenollosa was a foreigner hired from America to teach philosophy in Japan.

At first, he came to Japan to teach philosophy, but he felt a strong sense of crisis over the devastation of Japanese art.

He thought. ‘This is such a wonderful Japanese culture, why are the Japanese letting it fall into disrepair? I have to do something to revive Japanese art.’

During this period, the Japanese art philosopher Okakura Tenshin worked as Fenollosa’s assistant.

Okakura Tenshin could speak English and was well versed in Japanese art, so the two worked together from then on.

Then, Ernest Fenollosa gave a presentation on the excellence of Japanese painting viewed from abroad at a lecture hosted by the Ryūchikai.

Fenollosa said at that speech.

“Ladies and gentlemen, Japanese paintings are wonderful. Japanese paintings are more wonderful than Western paintings. You should have more confidence in their excellence.”

In this lecture, the term “Japanese painting” was used for the first time. It is surprising that it was a foreigner, not a Japanese, who used the term “Japanese painting” for the first time.

Ernest Fenollosa later left the Ryūchikai and founded an organization called the Kangakai with Okakura Tenshin.

The difference between the Ryūchikai and the Kangakai was that the Ryūchikai tried to preserve traditional Japanese painting as it was, while the Kangakai tried to improve traditional Japanese painting by adding the advantages of Western painting to create a new style of Japanese painting that would be accepted around the world. Ernest Fenollosa and Okakura Tenshin later became active mainly in the Kangakai.

As a result, two painters of the last generation of the Kanō school, Kanō Hogai and Hashimoto Gahō, were discovered at the Kangakai.

When Kanō Hogai was discovered by Ernest Fenollosa and Okakura Tenshin, there were already only 5-6 years left until his death.

After the encounter with these two men, Kanō Hogai started to improve his Japanese-style painting under the direction of Ernest Fenollosa in order to create a new style of Japanese-style painting at once, and produced a variety of works.

The works he produced in those few years are known as “The Dawn of a New Japanese Painting”.

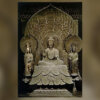

The most representative of these is “Hibo Kannon” (Avalokitesvara as a Merciful Mother).

This is an excellent piece – a favorite of mine, too.

This Buddhist painting depicts Avalokitesvara as a Merciful Mother in a realistic and mystical manner. It is said that this work was painted with Mary, mother of Jesus in mind.

Kanō Hōgai left behind a tremendous work of art that had never been seen before.

Unfortunately, Kanō Hogai died soon after producing that work.

If he had lived longer, I feel that the history of Japanese painting would have been different.

What happened after that was the establishment of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts in 1887, under the trend to catch up with and exceed Western paintings.

Okakura Tenshin was then appointed as the de facto first headmaster of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts.

From here he proceeded to have a variety of activities. It is no exaggeration to say that Japanese art revolves around Okakura Tenshin.

Okakura Tenshin preached a rather innovative ideal of Japanese painting to the next generation of Japanese painters at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts.

Okakura Tenshin himself was not a painter, so practical instruction was provided by Hashimoto Gahandō and Kawabata Gyokushō, and graduates of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts would be active in the art world in the future.

It looked like smooth sailing for Tenshin Okakura, but unfortunately, trouble occurred here.

That was the art school riot of 1898.