Murase Sōseki: A Key Painter Acting as a Bridge between the End of the Edo and the Modern Period in the Kyōto Art Circle

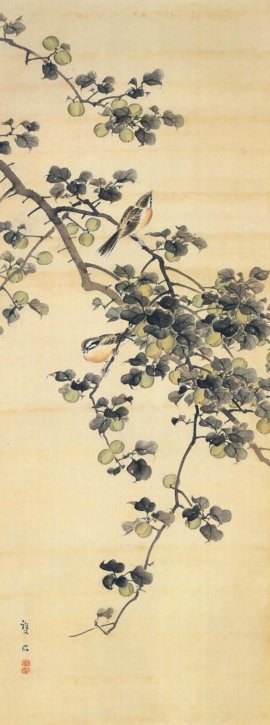

Small birds on Green Plum Tree

Murase Sōseki was a Shijō school painter, learned painting techniques under Oda Kaisen and Yokoyama Seiki, was one of the leading Shijō school painters active in the end of the Edo through the beginning of the Meiji period. He died in 1878 at the age of 56. He was skilled at bird-and-flower and landscape paintings. Murase Gyokuden was adopted as heir to Sōseki.

This painting ‘Small birds on Green Plum Tree’ is a bird-and-flower painting Sōseki was specialized in. Comparing with other Shijō school painters, he captured the objects for paintings in a more clear way, enabling us to feel the modern people’s sense of clarity toward things. The fresh seasonal sense of a summer’s beginning and the strong presence of green plums give us a favorable impression.

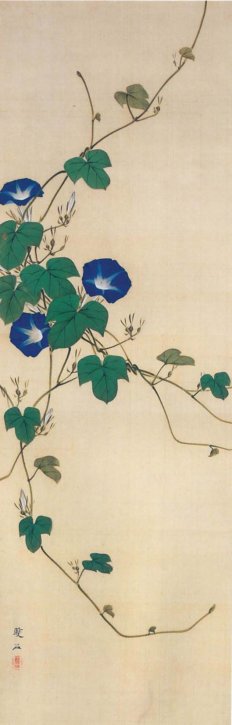

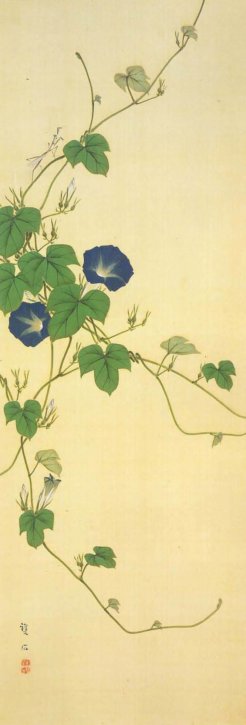

Morning Glories

In this painting ’Morning Glories’, three blue flowers and big green leaves are concentrated in the center-left part, thereby acting as the painting’s center of balance, with the vines stretching to the upper/down/right side. Skillfully placing the vines of morning glories only other than flowers and leaves strikes a subtle balance. The depiction of blue flowers and green leaves, both painted in cold colors, smartly conveys the atmosphere of a refreshing summer morning.

Butterflies in Spring Fields

‘Butterflies in Spring Fields’ is composed of simple depictions with Chinese milk vetches/dandelions/horsetails blooming in early spring fields on the left one and only a pair of cabbage butterflies hovering gracefully on the right one, giving us a poetic but friendly impression of peaceful spring fields.

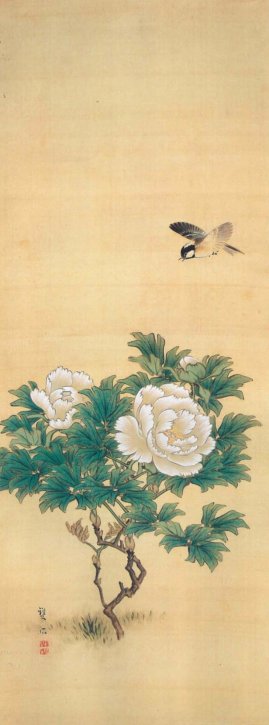

White Peonies and a Coal Tit

A Snowy Heron with Irises

The Maruyama school was initiated by Maruyama Ōkyo (1733-1795), while the Shijō school was founded by Matsumura Goshun (1752-1811). In accordance with Goshun’s first master, Yosa Buson’s will, Goshun became a disciple of Ōkyo after Buson’s death. Ōkyo had regarded Goshun as ‘Buson’s best disciple’ with due respect. Goshun in his youth as a disciple of Buson had drawn Southern Chinese (Nanga)-style paintings. His painting style, however, had changed drastically since he became a disciple of Ōkyo. Since then he had unfolded his own style as a Shijō school painter while appreciating Ōkyo’s painting style. It was Matsumura Keibun, younger brother of Goshun, that had established the Shijō school as one painting style. Thus, it is not inconsistent at all to deem the painting style called the ‘Maruyama-Shijō school’ to be one painting style, since two schools had flourished from the same trunk of a tree, Maruyama Ōkyo. Looking at the rise and fall of both painting schools, however, two schools had presented a marked contrast. As for the make-up of the Maruyama school, each of Ōkyo’s disciples such as Nagasawa Rosetsu, Watanabe Nangaku, Mori Tetsuzan, Oku Bunmei, Yamaguchi Soken, Gessen, and others had a strong personality and had not faithfully followed the Ōkyo’s painting style, rather translating what they had learnt from Ōkyo into their own works. As a result, each of their painting styles was no longer within the framework of the Maruyama school, but just one style based solely on each of their master-and-disciple relationships.

Looking at the Shijō school, on the other hand, Goshun’s painting style had been steadily succeeded to Matsumura Keibun, his younger brother, Okamoto Toyohiko, Shibata Gitō, Nagayama Kōin, further onto Yokoyama Seiki, a Keibun’s disciple, Shiokawa Bunrin, a Toyohiko’s disciple, and Kōno Bairei, a Bunrin’s disciple. This flow was nothing but the succession of the Shijō school’s painting style completed by Goshun and Keibun. Here we see the sharp contrast between the Maruyama school and the Shijō school in terms of their make-up. Furthermore, the difference in each school’s painting style had gradually disappeared. This had something to do with the fact that many of Ōkyo’s disciples emerged afterward had not so strong personalities as Ōkyo’s immediate ones. With the fusion of those two schools had emerged the modern Kyōto art circle. It was Murase Sōseki that had acted as a bridge between the end of the Edo and the modern period, as one of the painters standing just in-between.

‘White Peonies and a Coal Tit’, simply depicting one coal tit over one stump of peony is neat and clean, representing the typical works of the Shijō school. The composition – gorgeous peony’s flowers dominantly placed at the center of the painting effectively controlling the space and one coal tit as a decorative accent – follows one of the conventional Shijō school style.

‘A Snowy Heron with Irises’ depicts one snowy heron standing still at the root of a bunch of irises. The bird and flowers are placed like a kind of ‘dogleg’ shape with broad open space, effectively adding an allusive feeling. In the depiction of Irises extraordinary brush techniques are found on one hand, in the depiction of a snowy heron the traditional painting techniques of the Shijō school on the other.

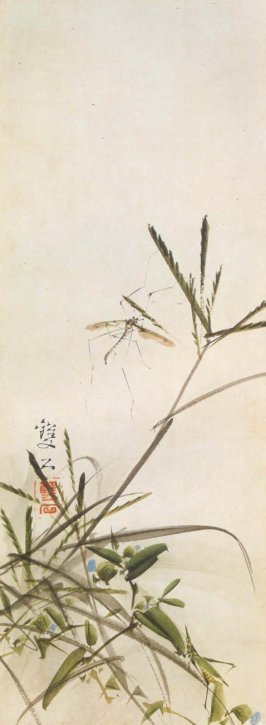

Autumn Grasses

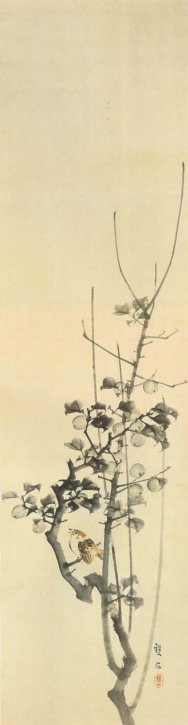

A Sparrow on Green Plum Tree

Morning Glories

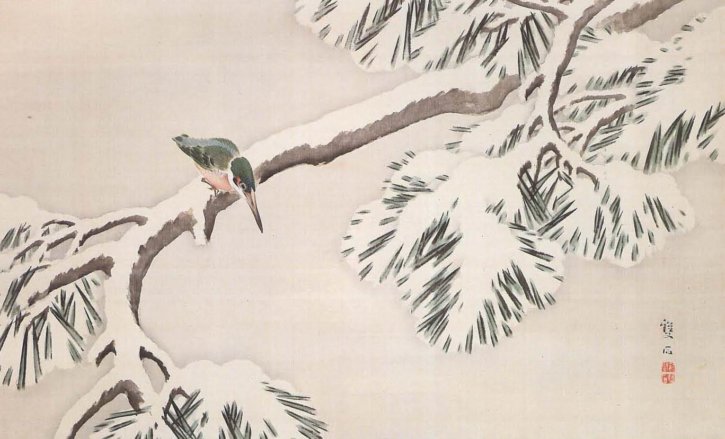

A Kingfisher on Snow-capped Pine Tree

A Praying Mantis with Chestnut Tree

Different from the Maruyama school branches, it was from the end of Edo through the Meiji period that the Shijō school branches had started to play a leading role in the Kyōto art circle. Moreover, they had spread their painting styles not only to Kyōto but also to the Edo art circle and other regions. In the meantime, painters who acquired the Shijō school style had become so much popular nationwide to the extent that it was no exaggeration to say, ‘the painting style of the Shijō school had spread throughout Japan’. One of the reasons for the spread of the Shijō school was that in comparison with the Maruyama school, the Shijō school was more blessed with prominent successors emerged afterward in the end of Edo period such as Okamoto Toyohiko, Yokoyama Seiki, Shiokawa Bunrin, Nakanishi Kōseki, Kōno Bairei, and others. Many painters gathered across Japan had become disciples of those prominent painters, learned painting techniques, and dispersed across the nation again. It is not hard to imagine that the works of famous painters and calligraphers like Maruyama Ōkyo, Matsumura Goshun, Ikeno Taiga, Rai San-yō, and others must have received an influx of orders across the nation. Their works were so popular that people had made tremendous efforts like using all of their connections they could think of at that time, for example, to buy Ōkyo‘s paintings or to ask San-yō to write some kanjis, Chinese characters. The rest of painters, however, had made tours around the nation with the help of wealthy persons or patrons, until they made themselves better known so that people would seek their works. In most cases those wealthy persons or patrons were from prestigious families or brewers/wealthy merchants in each region, enjoying by themselves literature and music as well as other creating works such as brush paintings, Haikai(seventeen syllables verse), and waka(thirty-one syllables poem) and others. Thus, painters stayed at wealthy people’s houses, drawing painting/calligraphy works and enjoying talks about art with those houses’ masters. It was not rare for painters to stay in the same house for as long as a half year. The life there used to be quite serene, since mass communication had not as developed as nowadays, with time flowing much more slowly. Through their tours backed by those wealthy persons or patrons, painters had conveyed various cultures directly to each region.

‘Autumn Grasses’ is quite simply composed, depicting two insects with nutsedges and Asiatic dayflowers – a landscape of very limited space at just one corner of a garden or a field, a completely ordinary scene without any unique features, which could be rather overlooked. Being exposed to this kind of painting depicting such an ordinary scene makes us reflect once again on our daily lives in which we are living in a hurry, overlooking the scene which we are familiar with. It is also one of the Shijō school’s distinctive features to depict quite ordinary and familiar scenes. The fact that those who had sought the Shijō school’s paintings were predominantly a kind of important local businesspeople had also helped develop such a unique feature. Depiction through the tsuketate brush painting technique gives this work skillful and professional rhythmic sense. The brush strokes with the techniques accumulated through the long-term training as a craftsman are so rhythmically running though. This work is a good example, displaying the full potential of Sōseki’s painting techniques by drawing the subject of a quite ordinary scene.

‘A Praying Mantis with Chestnut Tree’ likewise depicts only a part of the chestnut tree. Chestnut bursts on three branches of the tree – one cracked open with the chestnut showing up, the other one covered with the sharp prickles, another one depicted on the upper part only in a half shape – and a praying mantis at the back of a leaf is just an ordinary scene. Branches are stretching upward in the horizontally long painting, with the center of balance to the lower left. The rhythmical brush stroke is so skillful as to make us feel relieved. What he just happened to see was the scene of a praying mantis on the small branches of the chestnut tree in the autumn garden. Such a scene is just one of ordinary and familiar ones in nature, which must have inspired the sense of drawing for Sōseki.

‘A Sparrow on Green Plum Tree’ depicts with skillful painting techniques the scene of one sparrow sitting on the small branch of a plum tree with full of green plums. Rhythmic and skillful brush strokes with the light and shade of bluish sumi ink capture the tree/leaves/fruits of plums. Colored painting is used only in the depiction of a sparrow sitting on the small branch in the middle part of the painting, in which the bird looks quite lovely. The bird with its face looking diagonally upward, chirping for the coming of fellow birds serves as the focal point of the painting. Thin trunks and branches of a small plum tree stretching through the vertically long screen are depicted skillfully with only a single stroke of the side surface of the brush. The contrast by the light and shade of sumi ink conveys the dynamic sense of the fresh fruitful plum tree. The depiction in sumi ink of the plum tree probably in one evening scene of sunny weather during the rainy season reminds us of one twilight scenery with a painter sitting quietly at one corner of a front garden, sketching the plum tree.

The latter ‘Morning glories’ is depicted with the same techniques as those used in the former ‘Morning glories’. While this one depicts a pair of flowers, in the former one three flowers are drawn. Another slight difference in these two paintings is that a praying mantis is depicted on the vine only in the latter one. The fact that these two paintings are almost same except for these slight differences indicates those two must have been drawn in the almost same period. The fact also proves that the Shijō school painters, generally called as the sketch style painters, also had drawn paintings using the funpon technique-copying painting examples. Maruyama Ōkyo, referred to as the founder of the sketch style painting, had also used the funpon technique and his disciples as well had drawn paintings based on Ōkyo’s funpons. While one of the characteristics of the sketch style of Maruyama-Shijō school painters is that they had drawn paintings through real sketching, it was quite as usual for them to draw their paintings based on Ōkyo’s and other predecessors’ funpons. As for ‘Morning Glories’ as well, Sōseki probably completed one composition of work through the repeated sketching of morning glories. Once one composition was established as a base, he had drawn several similar paintings based on that composition using the same techniques. Those paintings were not totally in the same design, with each of them arranged to some extent. The former and the latter ‘Morning Glories’ are good examples of such a painting method. Lovely morning glories as if making us feel cool in a summer morning are depicted with skillful brushworks, showing Sōseki’s extraordinary painting techniques. Two paintings are well-composed with only vines skillfully placed without drawing the root part, representing familiar and typical works of the Shijō school.

‘A kingfisher on Snow-capped Pine Tree’ probably depicts a snowy morning – snow-covered branches bending downward with the weight of snow and green leaves of pine tree slightly shining in a fresh color. A kingfisher on the snow-covered branches is looking down with its beak down as if being about to fly downward to get some prey found in the snow. The snowy landscape is expressed with the part of accumulated snow unpainted, and only the part of green branches and background painted, making good use of the original color of silk canvas. Though this painting is not in scale term as large as ‘The Folding Screen of Pine Trees in the Snow’(a national treasure), one of Maruyama Ōkyo’s works, this painting skillfully depicting the accumulated snow on the branch of a pine tree, is an impressive one.